Stories of Sacrifice - POW/MIAs - 1LT Alexander R. Nininger (MoH) Final Part 5

THE ARMY HAD A PROBLEM. THE PUBLIC WANTED TO KNOW WHERE THEIR HERO WAS AND A NUMBER OF MEMBERS OF CONGRESS WANTED TO KNOW WHAT THE HELL WAS GOING ON.

THE ARMY HAD A PROBLEM. THE PUBLIC WANTED TO KNOW WHERE THEIR HERO WAS AND A NUMBER OF MEMBERS OF CONGRESS WANTED TO KNOW WHAT THE HELL WAS GOING ON.

Solving the case of 1LT Ira Cheaney was simple for the Army. They got some remains – any remains – and buried them at West Point and put Cheaney’s name on the headstone. Then they buried the records. Solved that problem for the next sixty years.

But the case of 1LT Alexander Nininger was much more complicated. As the first man awarded the Medal of Honor in World War II, public interest in his case was high. The government had used his heroism to boost American morale during the war’s darkest hour and now it was coming back to haunt them. They knew they better not screw this one up – again.

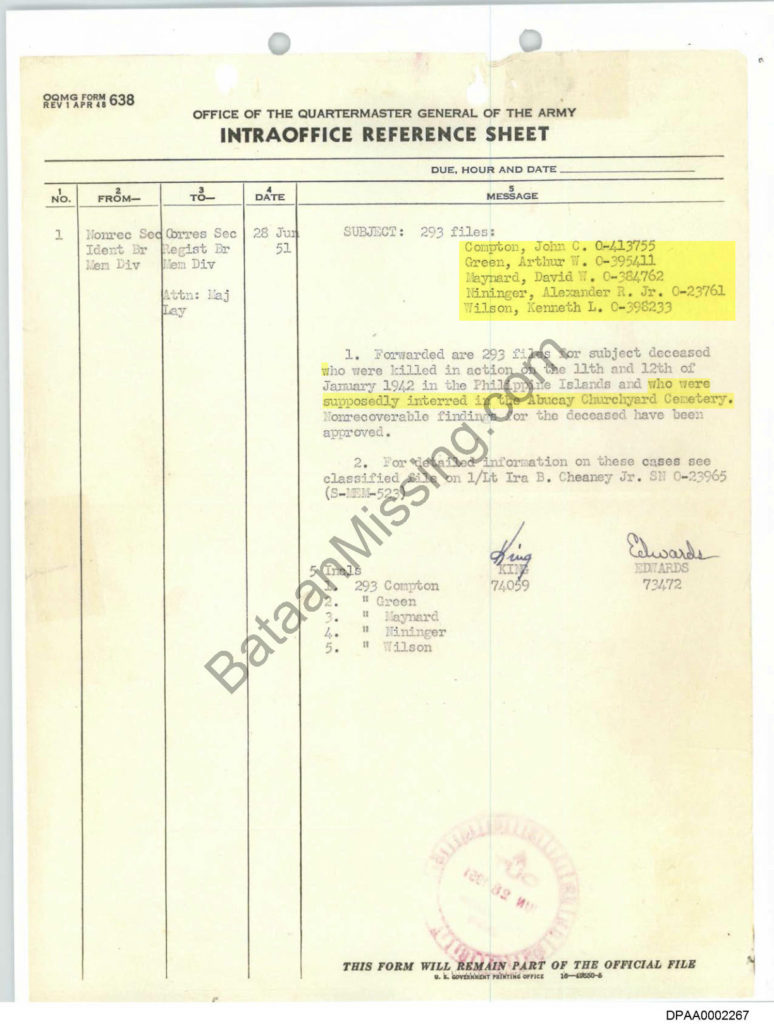

In addition, the families of four other officers who died in the same battle, and presumably would have been buried nearby, were demanding answers of their congressional representatives and they, in turn, were demanding answers from the Army. If just one of the five officers were identified there would be some explaining to do. They would have to identify all of them or none of them.

The Army’s problem then, and to this day, boiled down to one of credibility. To paraphrase Tom Holland, the former director of the JPAC Central Identification Laboratory, they were only as good as their last bad identification. If they admitted to making a mistake, every Gold Star Mother in the country would be wondering if they had actually received their son’s remains.

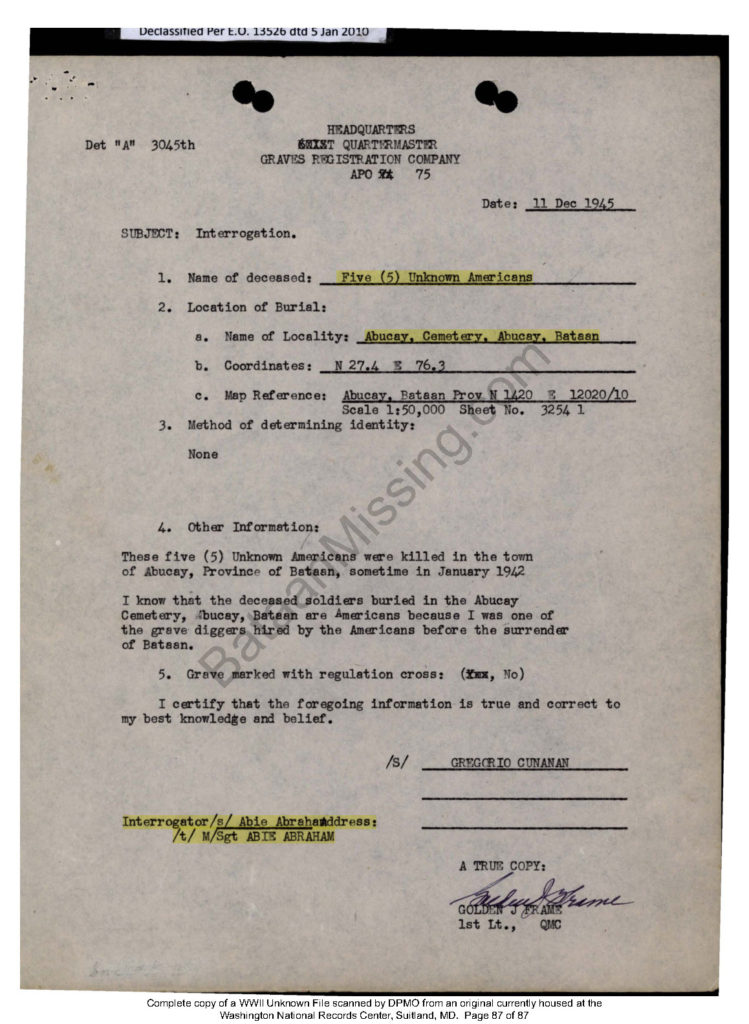

When the X-1130 remains were recovered from the Abucay Municipal Cemetery, they were immediately thought to be those of 1LT Alexander Nininger. But who did the other four sets of unidentified remains in that row belong to?

The files of each of those five Unknowns include identical statements from Gregorio Cunanan saying, “These five (5) Unknown Americans were killed in the town of Abucay, Province of Bataan, sometime in January 1942. I know that the deceased soldiers buried in the Abucay Cemetery, Abucay, Bataan are Americans because I was one of the grave diggers hired by the Americans before the surrender of Bataan.”

Unknown X-1130 had been immediately tagged as the remains of 1LT Alexander Nininger. In addition, there were four other young Philippine Scout officers who died in the same series of engagements that took Nininger’s life:

1LT John C. Compton

1LT Arthur W. Green

1LT David W. Maynard

1LT Kenneth L. Wilson

All five were members of Philippine Scout units and all five had died on 11/12 January 1942. In the absence of information to the contrary, it was reasonable to think that these five Unknowns were the five Americans buried by the local gravedigger, Gregorio Cunanan.

Soldiers Row of the Abucay Municipal Cemetery contained the remains of:

Grave 1, Unknown X3589 Manila #2, DoD Jan 42

Grave 2, Magno Caoit, 10302195 PS, DoD 12/18/41

Grave 3, Unknown X1051 Manila #2, DoD Jan 42

Grave 4, Victor F. Crowell, O2296, DoD 12/30/41

Grave 5, Cosimo A. Catanzaro, 37054718 PS, DoD 12/31/41

Grave 6, William Conway, 33034047, DoD 12/31/41

Grave 7, Magdaleno P. Burlaos, 10303868 PS, DoD 1/1/42

Grave 8, Unknown X1052 Manila #2, DoD Jan 42

Grave 9, Unknown X1130 Manila #2, DoD Jan 42

Grave 14, Leon Oropel, 10305917 PS, DoD Jan 42

Grave 15, Cenon Cruz, 10300723 PS, DoD 1/2/42

Grave 16, Maximo Jimenez, 6610984 PS

Grave 17, Marciano Ragaza, R6614250 PS

Grave 18, Unknown X1063 Manila #2, DoD Jan 42

(Graves 10, 11, 12 & 13 were not occupied)

In fact, it was so reasonable to think these five Unknowns were related, that to identify any one of them would have supported the identification of the others. The problem was that the Army’s proposed identification of X-1130 as 1LT Nininger had been disapproved by Washington because the parents of all of these men had been told by Colonel Clarke that they had been buried three-fourths of a mile away, in the Abucay Churchyard.

Even after multiple excavations of the Abucay Churchyard, no remains were found that could even be considered as those of Nininger, Wilson, Green, Compton or Maynard. None of them had been found in the churchyard and Washington had decreed that they were not in the Abucay town cemetery, so where were they?

The Army had a real problem. Because of Nininger’s receipt of the Medal of Honor, they had to be absolutely sure of the identification of his remains. At the same time, they would have to do some explaining if they identified any of the other four officers, but not Nininger.

By 1951, when Captain Vogl investigated the Nininger and Cheaney cases, the Army was beginning to realize they had a problem. They knew that Colonel Clarke’s information was incorrect because even after multiple excavations no remains had been found in the Abucay Churchyard that could be associated with any of the five officers.

Even after “looking” for seventy-five years and finding nothing, Washington still insists that Nininger was buried in the Abucay Churchyard and not in the Abucay Cemetery. Slow learners.

As recently as 2019, the government’s pros were massaging the evidence to support their theory that Nininger had been buried in the churchyard rather than the cemetery. Desperate to prove they had been right all along, they sent a team to Abucay to break open above ground tombs based on no more than a rumor that Nininger’s remains resided there.

The Army couldn’t go back and undo what they had worked so hard to screw up as they had backed themselves into a corner. The most important factor in identification of remains is credibility. If they fessed up to what they had done, it would cast doubt on tens of thousands of other identifications they have made. In their weird little bureaucratic minds it is better to deprive five families of the closure that would come with burying their sons than to cast doubt on all the other identifications they had pronounced the identities of, often with little or no substantiating evidence.

The mark of a good bureaucrat is that they are never wrong – just ask them.

Ultimately, the Army solved the problem by telling everyone to get their stories straight – or at least in agreement – and the written evidence of their misdeeds was classified as a defense secret and hidden away for a generation. Meanwhile, the Nininger, Cheaney, Maynard, Wilson, Compton and Green families are left with no answers and no closure. Their sons didn’t just fall off the face of the earth, but only the Army has the answers – and control of the remains – and they aren’t telling – or testing.

Over the years, the Army has excavated dozens of graves and broken open above ground tombs at the Abucay Church. They have exhumed the grave at West Point and found the remains to be “non-caucasian” in their attempt to prove that 1LT Nininger was buried in the Abucay Church yard and thereby prove themselves right.

The Army claims to be protecting the sanctity of the grave of X-1130, but that argument rings hollow considering the dozens of other graves they have disturbed in their quest to prove themselves to have been right.

Now, even in the face of repeated failures to find his remains and the overwhelming evidence that Unknown X-1130 is 1LT Nininger, they are unwilling to conduct DNA testing because it doesn’t fit their narrative.