Unarmed, Alone and Unafraid: The Silent Echoes of Baron 52

The jungle night was a void, swallowing all but the low growl of Baron 52’s engines, a U.S. Air Force EC-47Q slicing through the black skies over southern Laos on February 4, 1973. The mission was a secret carved in shadow, a Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) operation so covert it lived only in whispers, buried deep in Pentagon vaults. It was a mission that should never have happened. The Paris Peace Accords, signed on January 27, 1973, had promised an end to U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, mandating a ceasefire and the withdrawal of American forces within 60 days. By February, a fragile ceasefire in Laos, formalized on February 22, 1973, under the Vientiane Agreement, was meant to halt combat operations in the region, including U.S. air missions over Laos. Yet Baron 52 flew, defying the Accords’ spirit and the imminent Laotian ceasefire, its low, slow path over the Ho Chi Minh Trail a provocation in a war America was supposed to have left behind. The decision to fly—likely driven by the Pentagon’s desperate need for intelligence on PAVN movements along the Trail, North Vietnam’s lifeline for men and supplies—put eight men in the crosshairs of a conflict that refused to die.

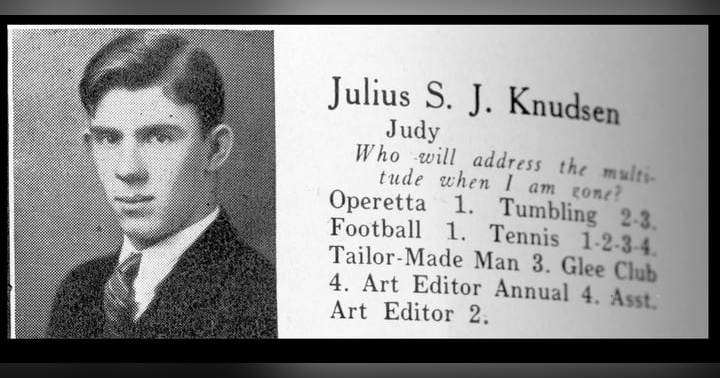

Up front, Capt. George Spitz gripped the controls, his eyes cutting through the dark for threats. Beside him, Lt. Severo Primm, the co-pilot, held the plane steady in restricted airspace. Lt. Robert Bernhardt plotted their course, his maps a lifeline in the chaos of Laos. Capt. Arthur Bollinger, a front-end crew member but stationed in the back as navigator, worked alongside the four back-enders of the 6994th Security Squadron, their motto “Unarmed, Alone and Unafraid” etched into their resolve: Sgt. Dale Brandenburg, coaxing life from the receivers; Staff Sgt. Todd Melton, Sgt. Joseph Matejov, and Sgt. Peter Cressman, hunched over NSA-designed radio equipment, sifting enemy signals from the static. Bollinger bridged the cockpit’s course with the back-enders’ SIGINT tasks, syncing navigation with their hunt for PAVN transmissions. These four back-enders were elite, handpicked by the US Air Force for the National Security Agency, trained for months at secret facilities to operate classified SIGINT gear, decode encrypted PAVN messages, and pinpoint troop movements that could shift the war’s fading pulse. They were fathers, sons, brothers—Todd with letters home, Peter locked on faint radio blips, Dale with a radio

I’m John Bear, a POW/MIA researcher and this case is my marrow. It’s not about files or maps—it’s about Joe Matejov, a radio operator from Long Island whose laugh could light a room, whose family entrusted me to tell his full story. They believe, as I now do, that the four back-enders—Brandenburg, Matejov, Melton, and Cressman—survived the crash and were taken prisoner by the North Vietnamese. A North Vietnamese radio transmission 5 1/2 hours post crash from Group 210, in the early morning hours of February 5, 1973, mentions captives near the crash site, 6 km north of the Huai Het River, 8 km east of PAVN Route 128, between Ban Bac and Cha Van. It’s not proof, but it’s a thread I’ve been steadily pulling since I promised the Matejovs and Bob Cressman I would find the truth, no matter how many doors I have to break.

The Baron 52 mission was a ghost in the war’s final days, a covert SIGINT operation that should have been grounded by the Paris Peace Accords and the Laotian ceasefire. The Accords, a diplomatic marathon led by Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho, aimed to end America’s longest war, mandating a ceasefire in Vietnam by January 28, 1973, and the withdrawal of U.S. troops. Laos, a sideshow in the conflict, was supposed to follow suit, with the Vientiane Agreement halting combat operations and barring all foreign military activity. Yet Baron 52 flew, a violation of the Accords’ intent, driven by the Pentagon’s fear of a post-Accords PAVN offensive along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The EC-47Q was a flying listening post, bristling with NSA tech—receivers, decoders, antennas—that could pluck PAVN signals from the ether, making it too tempting to ground. The back-enders, the 6994th Security Squadron, lived their motto: “Unarmed, Alone and Unafraid.” At NSA sponsored USAF facilities, they mastered classified systems, learning to parse coded chatter and relay intelligence under fire. Bollinger, though a front-ender, worked in the back, his navigation skills syncing the plane’s path with their SIGINT tasks. Their training was grueling—technical, psychological, forging men who could stay calm when the PAVN’s Flak Trap lit the sky. The 210th Triple A Battalion knew they were coming, their guns ready, exploiting the EC-47Q’s predictable path. That deliberate ambush cloaks the case in secrecy, burying evidence in classified vaults, making every step of my search a fight against shadows.

The Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, convened from August 2, 1991, to January 2, 1993, under the George H. W. Bush administration, was a crucible for truth. Chaired by Sen. John Kerry, a Vietnam veteran skeptical of live POW claims, and vice-chaired by Sen. Bob Smith, a New Hampshire Republican and Navy veteran, the committee probed the fate of missing servicemen, including Baron 52’s crew. Smith, whose father was lost in a World War II plane crash, became a fierce advocate for POW/MIA families, demanding transparency. His passion clashed with Kerry and Sen. John McCain, who prioritized normalized relations with Vietnam. Smith seized on the Group 210 intercept mentioning “four pirates,” pressing DIA analyst Robert Destatte for answers. In 1992, Destatte testified that the captives were likely ARVN helicopter crews shot down near the DMZ, citing geographic distance and lack of direct evidence linking them to Baron 52. By 1996, his memos shifted, claiming the captives were Lao Irregulars, a change that sparked skepticism for its inconsistency. Destatte’s 1992 testimony relied on vague correlations with ARVN losses, ignoring the intercept’s precise timing and location near Baron 52’s crash. His 1996 pivot to Lao Irregulars lacked primary source corroboration and dismissed that Lao captives typically went to Pathet Lao controlled reeducation camps, not North Vietnam, as the intercept suggests. Sedgwick Tourison, a former Army Security Agency and DIA intelligence officer, countered Destatte’s claims. His 1991 memos, prepared for the Senate committee, revealed that in February 1974, the DIA coded the Baron 52 back-enders as “KK” (died in captivity), while the Pentagon listed them as “BB” (killed in action, body not recovered). Tourison, who also exposed the abandonment of South Vietnamese spies in the 1960s, argued this discrepancy suggested the DIA knew of captures but withheld evidence, contradicting the Air Force’s stance that all died in the crash. Smith championed Tourison’s findings, pushing for declassification and believing the four back-enders were high-value prisoners due to their NSA training. The committee’s 1993 report found no “compelling evidence” of live POWs but noted unresolved cases like Baron 52, fueling Smith’s fight for the Matejovs and others.

My work is a grind, part detective, part historian, all stubborn dreamer. For over three years, I’ve sifted through declassified Pentagon files, PAVN records, and oral histories from JTF-Full Accounting and Stony Beach interviews. With John Matejov, Joe’s brother and the Primary Next of Kin, and Heather Atherton, a researcher as relentless as I am, I’ve mapped crash sites in a 20 to 30 km radius, tracing the 210th Triple A Battalion’s ambush along Route 128. I’ve chased names like Lt. Col. Luong Khanh Van, a political officer in the 377th Air Defense Division under the 471st PAVN Division, who might have processed prisoners that night. Every document is a clue, every interview a crack in the silence. The evidence screams crew survival: the Group 210 intercept, the crash site’s condition with broken trees suggesting a survivable impact, two crew revolvers buried uphill from the wreckage, and the back-enders’ training, which taught them to react fast in a crisis. No artifacts of Brandenburg—dog tags, gear, nothing—were found during the JTF excavation, bolstering the case for survival. Crash expert, USAF Col. (Ret.) Ralph Wetterhahn’s 2016 analysis suggests survivable G-forces for those in the rear. Yet the DPAA calls it closed, leaning on Destatte’s shifting claims. I don’t buy it. His ARVN and Lao theories crumble against the intercept’s precision, Tourison’s memos, and Smith’s advocacy.

The intercept is my north star. Wetterhahn’s report ties it to the crash. Dr. Jay Veith’s National League report notes American artifacts collected by the Vietnamese, hinting at more could be found. The parachute parts, enough for eight but with extras, keep hope alive. It’s a long shot, but my life’s built on long shots.

In early 2025, I drafted a rebuttal to the DPAA and DIA, shredding Destatte’s claims. I laid out the evidence: Wetterhahn’s analysis, the intercept, the revolvers, Brandenburg’s missing artifacts, Tourison’s memos, Smith’s push for answers. Lao Irregulars wouldn’t have been sent to North Vietnam; the back-enders’ NSA training made them high-value targets. I urged the case reopen. But paperwork doesn’t shift mountains. The truth needs a crowd, a loud chorus to rattle the Pentagon’s gates.

So I went public. I wrote a blog and a Facebook posts, building on a February 2025 article from The War Horse that laid bare the covert SIGINT mission, the Flak Trap, the crash softened by broken trees, and the families’ wait in the shadow of the Accords. My posts burned through social media, calling on veterans, families, and supporters to stand with the Matejovs. I shared Joe’s story—his thoughts of Marla, his NSA skills, his 6994th courage—and urged people to write congressmen, to keep the pressure on. The response was raw: veterans who flew EC-47Qs, families who knew loss, all saying, “Don’t let them fade.”

I pressed on, drafting a briefing for congressional leaders with Mike Henshaw, founder of the Asymmetric MIA Accounting Group. I asked for interviews with PAVN veterans like Major Hoang Dinh Cuu or Major Tran Hien De from the 210th AAA Regiment, follow-ups on FOIA requests I’d filed with John Matejov and Heather, and declassification of a dozen DIA documents flagged by the Air Force’s A1 office. I emailed our team, honing the pitch to be firm yet collaborative, urging the Vietnamese Office for Seeking Missing Persons to locate these PAVN veterans. The back-enders’ NSA training made them prime interrogation targets, especially after a Flak Trap. Honey catches flies, but my patience is fraying.

The road’s been brutal. The DPAA offers only silence or excuses. U.S. archives are a labyrinth, missing HUMINT reports buried by the mission’s secrecy and the Accords’ fallout. I’ve hit walls—bureaucrats shrugging, agencies dodging—but I don’t break. I’m planning to tap DIA’s Stony Beach for PAVN veteran interviews, men who might recall a SIGINT plane caught in their Flak Trap. Nights find me staring at maps, seeing the crash site, the broken trees cradling the wreck. Did Joe’s thoughts of Marla keep him going? Did the 6994th’s motto drive them? Those questions burn, but they drive me.

This fight stretches beyond Baron 52. It’s tied to men like Major William Brashear, an F-4C Phantom pilot shot down in 1969 by a PAVN AAA unit near Binh Tram 44. Captured, he was taken to a PAVN field hospital under Binh Tram 36, treated for serious burns, then transferred to Binh Tram 35, where his trail goes cold. On my podcast, Stories of Sacrifice: American POW/MIAs, I tell their stories—Joe’s dreams of Marla, Todd’s letters, Peter’s focus, Dale’s hands, Art’s logs bridging front and back. I share the evidence—the intercept, the revolvers, the parachutes, Tourison’s memos, Smith’s fight—hoping for a lead. I built a dossier and press release, leveraging The War Horse investigation to spotlight survival and capture, urging the Pentagon to chase leads, pitching it to news outlets with urgency.

In my dreams, I see them—Joe at his radio, dreaming of Marla, Peter listening, Todd writing, Dale working the receiver, Art syncing the mission, the 6994th’s “Unarmed, Alone and Unafraid” in their blood. Four survived, their training a lifeline, caught in the PAVN’s trap. They didn’t vanish. They’re out there, in the truth, waiting. And I won’t let them fade.

Learn more about Joe’s story and please share! The more who read it, it may help bring Joe home. Still Searching: Story Man Seeks Truth About Brother’s Vietnam War Disappearance