The Unsung Hero: The Life, Sacrifice, and Enduring Legacy of Brigadier General Guy O. Fort

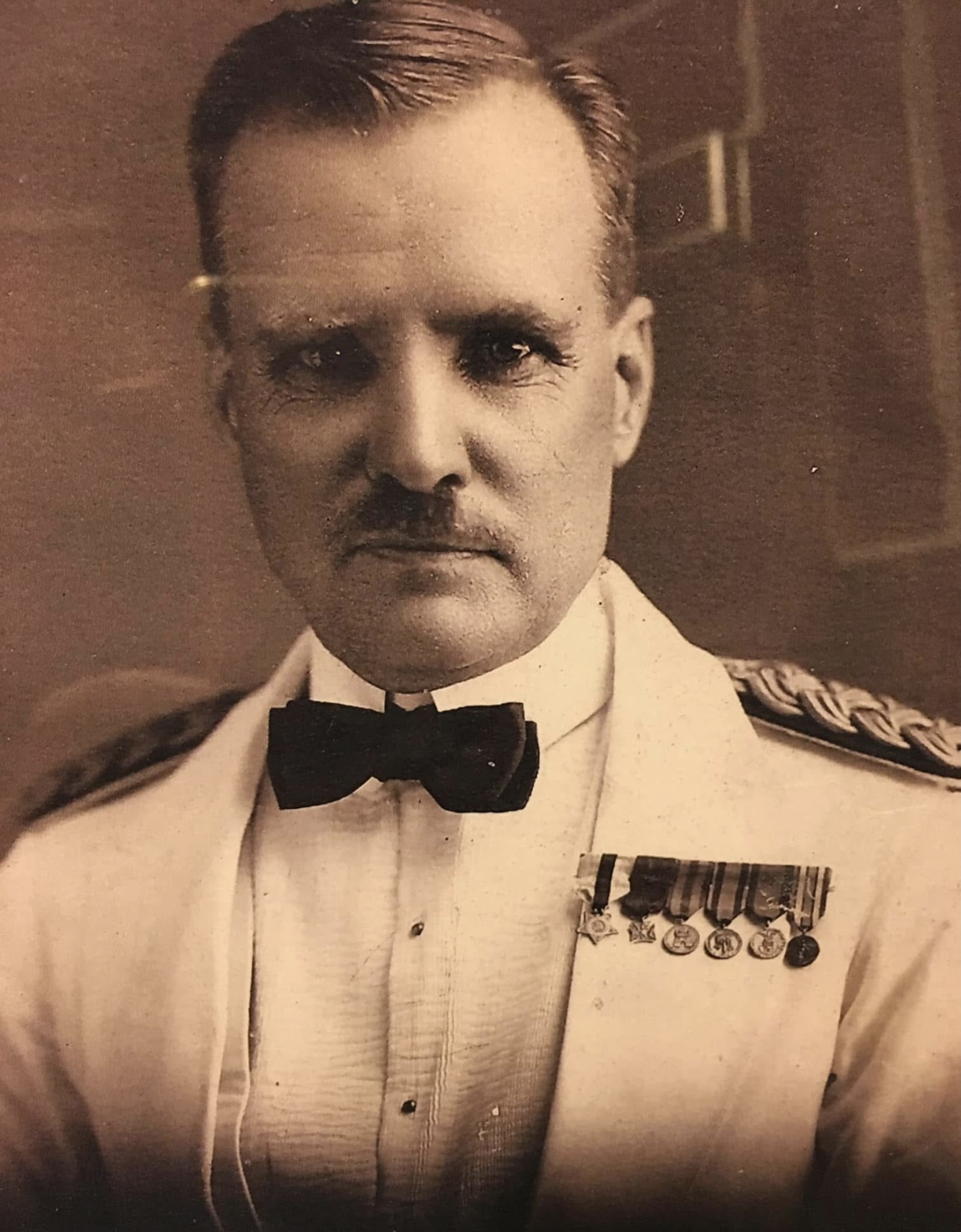

In the annals of American military history, few stories capture the essence of unwavering duty, cultural empathy, and ultimate sacrifice quite like that of Brigadier General Guy O. Fort. Born in the late 19th century, Fort’s life spanned pivotal eras of U.S. expansion, colonial administration, and global conflict. He rose from a humble enlistee to a respected commander in the Philippines, where he forged deep bonds with local communities, particularly the Moro people of Mindanao. His tragic execution during World War II at the hands of Japanese forces marked him as the only American-born general officer to be killed by the enemy in such a manner. Today, as we reflect on his story, recovery efforts continue to bring closure to his family and honor his remains. Drawing on newly reviewed statements from war crimes trials, including eyewitness testimonies and confessions from Japanese officers, join me as we delve into the remarkable journey of this forgotten hero—a man whose defiance in the face of death echoed his lifelong commitment to freedom and alliance.

Early Life: From Michigan Roots to Philippine Shores

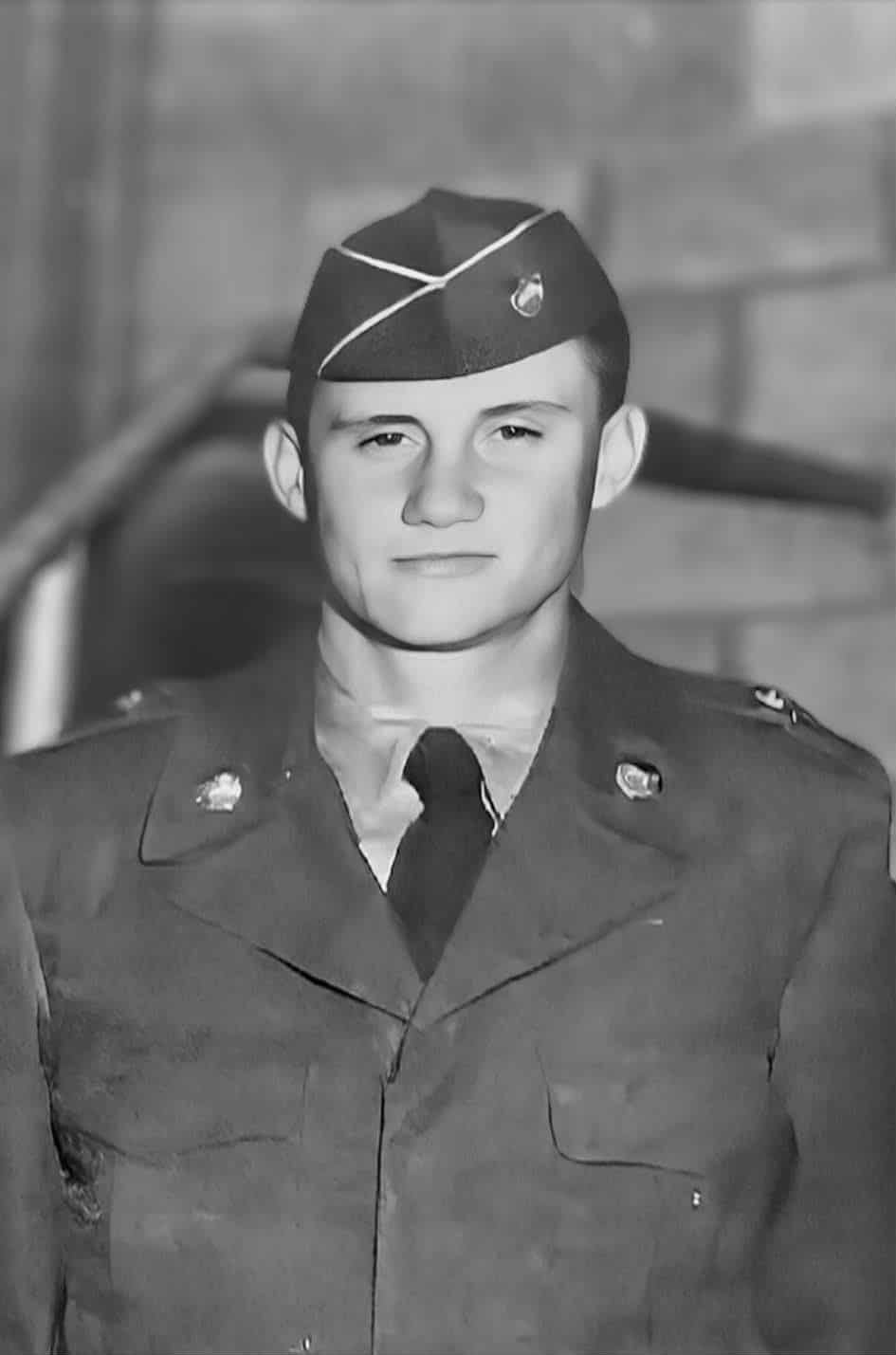

Guy Osborne Fort was born on January 27, 1879, in Kellerville, Michigan—an area now part of Traverse City—to Jacob Marvin Fort and Lena Fulkerson. Growing up in a modest family, the Forts later relocated to Gloversville, New York, where young Guy developed a sense of adventure and resilience that would define his future. At the age of 20, amid the fervor of the Spanish-American War and its extension into the Philippine-American War, Fort enlisted in the U.S. Army on March 24, 1899. Described in enlistment records as having blue eyes, light brown hair, a fair complexion, and standing at 5 feet 7½ inches tall, he was assigned to Company D of the 4th Cavalry and later Company A of the 15th Cavalry, shipping out to the Philippines.

This initial deployment thrust Fort into the heart of America’s imperial ambitions in the Pacific. The Philippine-American War (1899–1902) was a brutal conflict pitting U.S. forces against Filipino nationalists seeking independence after the defeat of Spanish colonial rule. Fort served honorably for three years, witnessing the complexities of occupation and counterinsurgency. He was discharged on November 26, 1902, at Paranq, Mindanao, with an “Excellent” character of service. Rather than returning home, Fort chose to stay in the Philippines, captivated by its diverse cultures and landscapes. This decision set the stage for a career deeply intertwined with the archipelago’s fate.

Building a Career in the Philippine Constabulary

In 1904, Fort re-entered military service, this time as a 3rd Lieutenant in the Philippine Constabulary—a gendarmerie-style police force established by the U.S. to maintain order in the newly acquired territory. The Constabulary was instrumental in suppressing the Moro Rebellion (1899–1913), a series of uprisings by Muslim Moro groups in the southern Philippines resisting American rule. Fort’s postings were primarily in Mindanao, where he immersed himself in local customs. He studied the rituals, languages, and traditions of the Moro people, earning a reputation as an expert on their society. His approach was unconventional for the era: rather than relying solely on force, Fort negotiated with outlaw bands, convincing many to lay down their arms through dialogue and respect.

During the 1930s, as the Great Depression gripped the U.S., Fort contemplated retirement and repatriation but hesitated due to bureaucratic hurdles, including the lack of a birth certificate. His last letter home, dated April 1939, reflected a man content with his adopted homeland yet aware of gathering storm clouds in the Pacific.

World War II: Command and Resistance in Mindanao

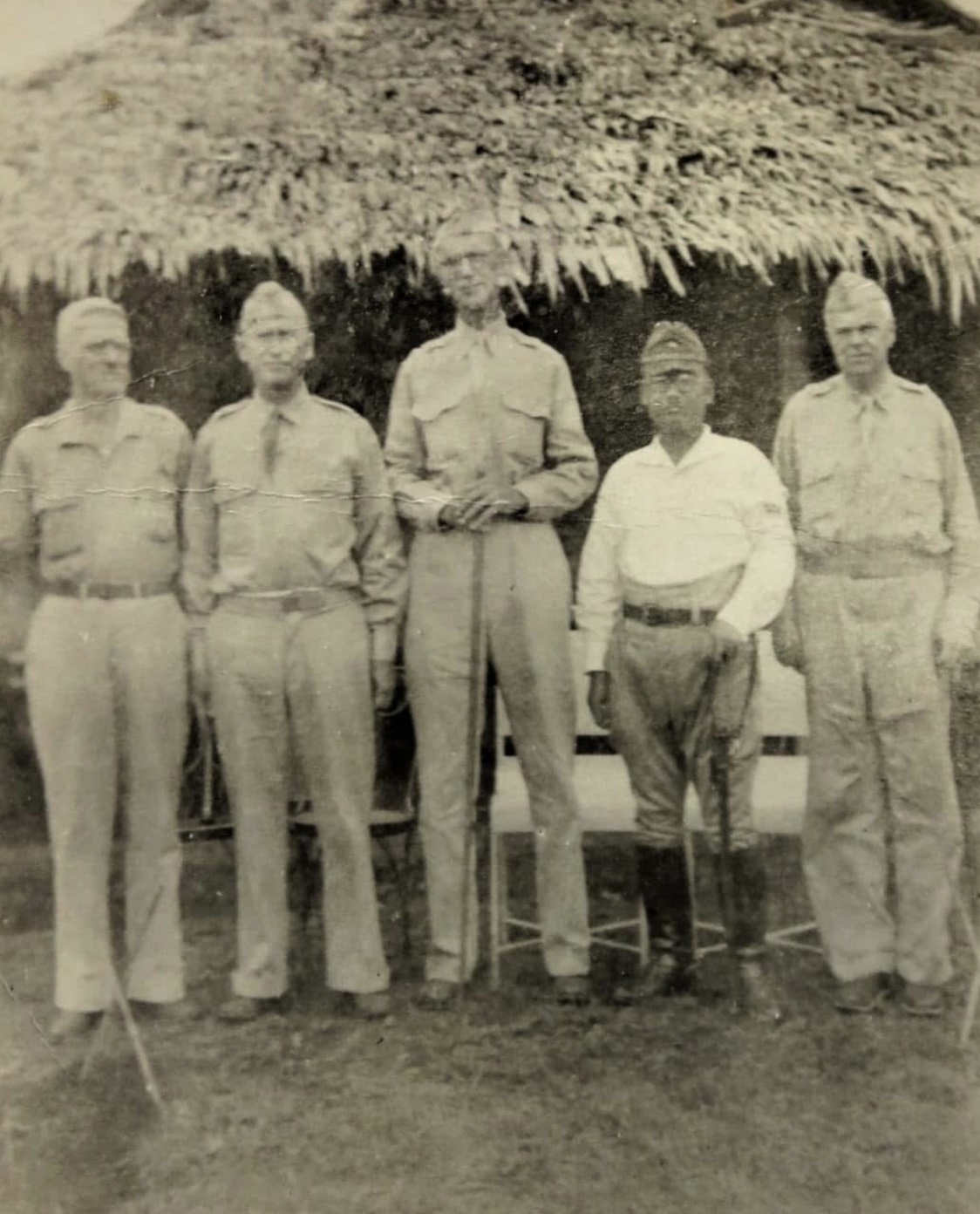

As tensions escalated with Japan, Fort’s expertise made him invaluable. In November 1941, the Philippine Constabulary integrated into the Philippine Army under the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). Fort, now a Colonel, was assigned to command the 81st Division (Philippines) and dispatched to Bohol. On December 20, 1941—just days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor—he was promoted to Brigadier General. He relocated his division to Lanao province in Mindanao, where he organized battalions of Moro soldiers, leveraging his longstanding relationships with the Maranao and other Moro groups.

Fort’s preparations were prescient. He planned a defense in depth and trained his forces for guerrilla warfare, anticipating conventional defeat against a superior Japanese army. Combat erupted on April 29, 1942, with the 81st Division inflicting heavy casualties on the invaders through ambushes and demolitions that blocked key roads. His unit fought longer than many others, embodying the fierce resistance of Filipino-American forces. However, overwhelmed, Fort received surrender orders from higher command on May 27, 1942. He protested vehemently but complied, though he allowed Moro fighters to retain U.S. rifles and equipment for continued guerrilla operations—a move that fueled ongoing resistance.

Following the surrender, Fort and approximately 46 American and 300 Filipino prisoners were interned at Camp Keithley in Dansalan (now Marawi), a former U.S. base turned Japanese prison camp. Conditions were dire, with meager rations and constant threats of violence. On July 3, 1942, tensions escalated after the escape of four prisoners from the camp, prompting the Japanese to select four officers for retaliatory execution as a warning to the others. Among those chosen was General Fort himself. According to the eyewitness account of Ben Hagans, a young American boy interned with his family who later shared his oral history with the National WWII Museum, the prisoners were forced to assemble and watch as the Japanese tied the selected men to wooden stakes. Hagans vividly recalled: “They put General Fort at a stake. Colonel Vesey told them to take him down he would take the General’s place.” Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Vesey, a West Point graduate and close friend of Fort’s, stepped forward in an act of profound selflessness, offering his life to spare the general’s. Vesey, along with Captain Albert Price and First Sergeant John Chandler, were then bayoneted repeatedly in a slow, torturous execution that lasted hours, their screams echoing through the camp. Hagans noted that Vesey lingered in agony, taking several hours to die from his wounds. This harrowing event, meant to instill terror, instead highlighted the unbreakable bonds of camaraderie among the captives and left an indelible scar on survivors like Hagans, who was just 12 years old at the time.

War crimes trial testimonies, such as that from Edward M. Kuder, a civilian administrator who gathered accounts from survivors like Lt. Banning and Sgt. Mapes, corroborate Hagans’ recollection. Kuder detailed how the escape of Sgt. Ball, Johnson, Smith, and Knortz infuriated the Japanese under Col. Yoshinari Tanaka, leading to the selection and bayoneting of Vesey, Price, and Chandler near Signal Hill in Camp Keithley. Lt. Col. Tiburcio Naidas, a Philippine Army officer and POW, also confirmed the incident, noting that the three were held as hostages and never returned after being taken away.

The very next day, July 4, 1942—a date laden with cruel irony for American prisoners—the Japanese forced the remaining POWs, including Fort, to embark on what became known as the Iligan Death March (also referred to as the Mindanao Death March or Dansalan Death March). This grueling trek covered approximately 25 to 36 kilometers from Camp Keithley in Dansalan to Iligan in Lanao del Norte, with the ultimate destination being Camp Casisang in Malaybalay, Bukidnon. Under the blazing tropical sun, the prisoners were denied transport trucks that were readily available, instead marching on rocky dirt roads without food or water. American POWs were tied together with gauge wire through their belts, while many Filipinos walked barefoot, their feet blistering on the hot ground. Exhaustion claimed many; those who collapsed were often shot in the forehead to prevent them from potentially joining guerrilla forces if they recovered, as recounted by survivor Victor L. Mapes: “Those who fell were left behind after they were first shot at the forehead to prevent them from joining the guerrillas in case they recover.” Notable atrocities included the shooting of Major Jay J. Navin, who fell from fatigue and was executed by a Japanese guard, and American civilian Mr. Childress (or Kildritch), who was dragged aside and shot twice to ensure his death. Estimates suggest 10 to 12 Filipino soldiers were killed by bayoneting or shooting during the march. Fort endured this ordeal, his leadership and resilience helping to sustain his fellow prisoners amid the horror. Mockingly dubbed the “Independence Day March” by some survivors, this event stands as one of only two death marches recognized in the Tokyo war crimes trials as evidence of inhuman treatment of POWs.

The Tragic Execution: Defiance Until the End

In November 1942, Japanese authorities, facing a renewed Moro rebellion in Mindanao, sought Fort’s cooperation to quell the uprising. They transported him back to Marawi (then Dansalan) and paraded him through the streets, pressuring him to broadcast a surrender appeal to his former allies. True to his principles, Fort refused, declaring, “You may get me, but you will never get the United States of America.” On November 11 (or 13, per some accounts), 1942, under orders from Lt. Colonel Yoshinari Tanaka, Fort was executed by firing squad. Reports indicate he was tortured prior to his death, making his end one of the most harrowing among American commanders in WWII.

Tanaka was later convicted by an Allied war crimes tribunal and hanged at Sugamo Prison on April 9, 1949. Fort’s execution sparked revenge attacks by Moro guerrillas against Japanese forces, underscoring the loyalty he had inspired. He remains the only U.S.-born general executed by enemy forces in the war.

Petronio C. Encabo, a Filipino POW who served as an errand boy for Japanese officers, provided a detailed eyewitness account in his 1946 testimony. Encabo described seeing Fort brought back to Dansalan in late October 1942, guarded by Kempeitai under Sgt. Ninoma. On November 11, he witnessed Fort being forced to sign a propaganda message urging Filipinos to surrender, typed by Lt. Jose Lukban. Encabo read the stencil: “TO THE FILIPINO PEOPLE: THE UNITED STATES ARMY IN THE PHILIPPINES HAS BEEN DEFEATED. THE AMERICAN NAVY IN THE PACIFIC HAS BEEN OVERWHELMED. FILIPINOS, AMERICA HAS LOST HER ASIATIC HOPE. SURRENDER AND FOLLOW THE GUIDANCE OF NIPPON AT THE EARLIEST TIME FOR THE SAKE OF PEACE.” Later that afternoon, Encabo saw Japanese officers—Y. Muruta, Nakao, and Maj. Hifumi Hiramatsu—selecting swords, followed by Col. Tanaka’s arrival. Fort was tied to a truck with his wrists bound and body secured, guarded by over ten Kempeitai with fixed bayonets, and driven toward Iligan.

That evening, Encabo noted the return of wet-clothed officers, including Ninoma and Hiramatsu. The next day, interpreter Harada confided that Fort had been blindfolded, read scripts by Tanaka, shot twice, and stabbed by Hiramatsu as he gasped for breath. Encabo saw mimeographed copies of the message bearing Fort’s signature, which he recognized as genuine. He believed the execution occurred at the landing field behind Signal Hill in Camp Keithley.

Interrogations of Japanese officers further illuminate the events. Lt. Col. Tanaka confessed in 1948 to ordering the executions of Vesey, Price, and Chandler for the escape, and Fort on Ikuta’s orders, executed by shooting near the firing range. Sgt. Maj. Kiyoshi Arai and interpreter Masaji Komatsu detailed Fort’s interrogation and execution, confirming Tanaka’s involvement and the site’s location.

Legacy and Honors: A Family’s Quest for Closure

Fort’s posthumous awards reflect his valor: the Distinguished Service Medal, Purple Heart, Prisoner of War Medal, American Defense Service Medal, World War II Victory Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and Philippine Defense Medal. His name is inscribed on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery, as his body was never officially recovered by the U.S. government. However, former POW and provincial governor Ignacio S. Cruz claimed to have located and handed over Fort’s remains to the American Graves Registration Service.

In 2017, Fort’s granddaughter, along with families of other missing soldiers, sued the U.S. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency to exhume and identify remains. Under pressure from the families, the DPAA exhumed the remains from the unknown graves that Ignacio S. Cruz had turned over. However, scientific analysis determined that these remains were not those of Fort or the other executed soldiers, Vesey, Price, or Chandler. This finding underscores the ongoing challenges in accounting for WWII missing personnel and reinforces the need for continued independent efforts. As of August 30, 2025, organizations like the Asymmetric MIA Accounting Group (AMAG) continue efforts to locate and repatriate Fort’s body, drawing on eyewitness accounts from survivors like Ben Hagans to pinpoint execution sites in Marawi. These missions highlight Fort’s enduring impact as a bridge between American and Filipino histories. War crimes trials exposed the atrocities, leading to Tanaka’s conviction and shedding light on the brutality faced by POWs.

Fort’s story also influenced U.S. special forces development, as his guerrilla tactics with Moro allies prefigured modern unconventional warfare. Historians remember him as a champion of U.S.-Philippine unity, a man who lived among the people he protected and died defending their shared ideals.

Our Upcoming Mission: Hope in a Volatile Land

This fall, our all-volunteer AMAG team is heading to Marawi, the site of former Camp Keithley. It’s no easy task—the area was devastated by a five-month ISIS battle in 2017, making it volatile even now. But led by Mike Henshaw, our founder and a 25-year Army veteran, we’re committed. Mike has recovered over 100 missing servicemen, driven by an unbreakable sense of duty. I’ve spent countless hours cross-referencing wartime maps, records, and Ben’s accounts to narrow down search sites. With ground-penetrating radar we have a genuine chance at locating skeletal remains, even after 83 years.

At AMAG, we’re actively supporting Fort’s granddaughter Barbara Fox in her quest for closure, working closely with her to honor her grandfather’s legacy through this mission. For families like Barbara’s, this means everything—holding a tangible piece of their history, honoring General Fort’s sacrifice. The Vesey, Price, and Chandler families deserve to know their loved ones’ acts of endurance and selflessness aren’t lost to time. Ben is astonished these families still await closure; he relives Vesey’s screams, Fort’s defiance, the beatings, the march, and his mother’s suffering in his dreams. Yet, his resolve to honor them fuels us.

How You Can Help Bring Them Home

This is where you, our supporters, come in. Mike, myself, and the AMAG team do this work voluntarily, out of love and duty for those who gave all. But tools like ground-penetrating radar, travel to Marawi, and forensic analysis require funding. Head to AMAGonline.org and donate today—every contribution brings us closer to repatriating Fort, Vesey, Price, and Chandler. Imagine the moment a family receives that closure, a hero’s name shifting from a memorial wall to a grave with full honors. Your support makes that possible. Join us, follow our progress, and ensure these men are remembered.

Mission Mindanao- More on our recovery mission this fall.

Conclusion: Remembering a Hero’s Defiance

Brigadier General Guy O. Fort’s life was a testament to adaptability, empathy, and courage. From his Michigan birthplace to the jungles of Mindanao, he embodied the best of American service abroad—respecting cultures while upholding duty. His final words resonate as a beacon of resistance against tyranny. As we honor veterans today, let’s remember Fort not just for his sacrifice, but for the alliances he built that outlasted him. If you’re inspired, support groups like AMAG in their quest to bring him home. What stories like his teach us is timeless: true heroism lies in standing firm, even when the end is near.

Thank you for reading and for standing with us. Let’s bring them home.

— John Bear, Chief of Research, AMAG