Reassessing the Baron 52 Incident: Evidence for Survival, Capture, and the Imperative for Renewed Investigation

Executive Summary

The Baron 52 incident, involving the shootdown of a U.S. Air Force EC-47Q electronic reconnaissance aircraft over southern Laos on February 5, 1973, stands as one of the most contentious unresolved casualty resolution (UCR) cases from the Vietnam War. Occurring just days after the Paris Peace Accords, the event highlights the complexities of post-ceasefire intelligence operations and the enduring challenges in POW/MIA accounting. The Department of Defense (DoD) (now called Department of War (DoW)) and Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) have maintained a Killed in Action (KIA) Resolved designation for all eight crew members, largely based on the 1993 Joint Task Force-Full Accounting (JTF-FA) crash site excavation. However, an exhaustive analysis of declassified documents, forensic accident reports, signals intelligence (SIGINT), and historical records reveals substantial evidence suggesting that four back-end crew members may have survived the crash and been captured by People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) forces.

This report draws on a wide array of primary and secondary sources, including declassified National Security Agency (NSA) intercepts and correlation studies, crash dynamics analyses, search-and-rescue (SAR) testimonies, Senate Select Committee (SSC) investigations, and PAVN order of battle (OOB) memoirs. Key findings include:

- A survivable descent with survivable impact forces, and physical indicators of egress with post-crash activity.

- Contemporaneous PAVN radio intercepts, explicitly correlated by NSA to Baron 52 under Reference Number (REFNO) 1983, describing the capture and movement of four “pirates” (a code for American pilots).

- Inconsistencies in Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) analyses that dismissed the intercepts’ relevance, potentially leading to withheld intelligence from the Military Casualty Review Board and a premature group burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

- Identification of implicated PAVN units (210th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Regiment, 377th Air Defense Division, 471st Division) and personnel (e.g., Lt. Col. Luong Khanh Van), offering actionable leads for further inquiry.

The evidence supports a High probability of initial survival and capture for the four back-end crew members, underscoring systemic flaws in the U.S. accounting process, such as intelligence compartmentalization, post-accords diplomatic pressures, and underutilization of SIGINT. To address these gaps and provide closure, the DoW and US Air Force must reevaluate the case and allocate resources for collaboration with the Vietnamese Office for Seeking Missing Persons (VNOSMP) to interview surviving veterans from the 210th, 377th, and 471st units. This non-invasive approach leverages strengthened U.S.-Vietnam relations and aligns with the nation’s commitment to the “fullest possible accounting.”

This analysis integrates insights from over 50 sources, including SSC depositions, declassified NSA documents, US and PAVN veteran accounts, to build a compelling, evidence-based argument accessible to policymakers, families, and the public.

Introduction: The Baron 52 Incident in Historical Context

The Vietnam War’s conclusion was marked by the Paris Peace Accords of January 27, 1973, which mandated a ceasefire, U.S. troop withdrawal, and the repatriation of prisoners of war (POWs). However, the accords did not halt all hostilities, particularly in Laos and Cambodia, where the U.S. continued covert reconnaissance to monitor North Vietnamese Army (NVA) movements along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This supply route, critical for PAVN logistics into South Vietnam and Cambodia, remained a flashpoint despite the fragile peace accords.

Baron 52, an EC-47Q aircraft modified for electronic warfare and signals intelligence (SIGINT), exemplified these ongoing operations. Operated by the 361st Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron (TEWS) with back-end specialists from Detachment 3 of the 6994th Security Squadron, the plane was tasked with the highly classified NSA equipped airborne radio direction finding (ARDF) equipment to intercept enemy communications. Late in the evening on February 4, 1973, Baron 52 departed Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base (RTAFB) for a “Midnight Smoker” mission over Saravane Province.

The crew of eight included:

- Front-end flight personnel: Capt. George R. Spitz, 1st Lt. Severo J. Primm III, 1st Lt. Robert E. Bernhardt, Capt. Arthur R. Bollinger.

- Back-end electronic operators: Sgt. Dale Brandenburg, Sgt. Peter R. Cressman, Sgt. Joseph A. Matejov, SSgt. Todd M. Melton.

At approximately 1:40 a.m. local time on February 5, the aircraft reported anti-aircraft fire before contact ceased. The plane crashed on a densely jungled mountainside in Saravane Province, coordinates approximately 15°30’N 106°45’E. This incident occurred amid diplomatic sensitivities, as the U.S. sought to avoid actions that could derail the accords or expose ongoing covert activities.

Initial SAR efforts discovered the crash site on February 7. Jolly Green helicopters reached the site on February 9th for a limited 40-minute ground inspection due to enemy threats. The team, including CMSgt Ronald Schofield (6994th technician), reported three charred front-end remains in the cockpit, the disputed fourth, and no back-end evidence. The plane’s upside-down fuselage, burned post-crash to an 18-inch tube, showed signs of post-crash looting and scavenging.

The US Air Force’s rapid KIA-Body Not Recovered (KIA-BNR) designation three weeks later—despite lacking compelling death evidence and inconsistent with standard casualty procedures—raised serious questions, as noted in Sedgwick Tourison’s 1991 SSC memo. The 1993 JTF-FA excavation and 1995 closure as KIA, leading to a group burial at Arlington, were influenced by DIA senior analyst Robert Destatte’s conclusion that related PAVN intercepts were unrelated, withholding them from review by the Military Casualty Review Board. Declassified materials since 1992, including NSA intercepts declassifications and SSC investigations, challenge this narrative, prompting this reevaluation.

Evidence of Crash Survivability

The survivability of Baron 52’s crash is a cornerstone of the argument for reevaluation, supported by forensic, dynamic, and eyewitness data indicating a high probability that the four back-end crew members escaped the initial impact. Ralph F. Wetterhahn’s 2016 crash analysis (Crash Analysis & Evidence of Survival.pdf), a 10-page report by a retired USAF colonel and accident investigator, reconstructs the sequence using site photos, wreckage patterns, and EC-47Q specifications.

Wetterhahn determined the aircraft sustained radar-directed AAA damage (likely 57mm or 85mm) initiating a rapid but survivable descent. Impact occurred at a shallow 10-15 degree angle, speed 100-170 knots, producing 2-5 G-forces—survivable for the rear crew, positioned lower and aft of the main fuel cells. The tail separated, and the rear cargo door was removed creating an egress path. Probability: Very High for back-end survival (70-80%), as the wings absorbed primary impact.

The 1993 JTF-FA excavation recovered wreckage pieces (heavily scavenged for metal pre-excavation), including 23-31 bone fragments (some non-human), one partial tooth (Cressman’s, forensic ID without DNA), dog tags (one of Matejov’s), parachutes (22 V-rings from 7+), and pieces of nomex flight gear absent any long zippers. Notably, four .38 caliber Smith & Wesson revolvers were found, two buried together 50 meters northeast/uphill (20-degree incline), inconsistent with natural scattering—indicating deliberate survivor action (e.g., concealment). Five lap belt buckles were recovered, three locked, two open, suggesting post-impact unbuckling by at least two individuals.

SAR testimony from CMSgt Ronald Schofield (August 11, 1992, SSC deposition, LOC frd/pwmia/295/91954.pdf) corroborates: During the February 9 ground insertion (40 minutes), he observed three charred front-end remains (Spitz left seat, Primm right, Bernhardt jump seat with partial recovery of his remains), identifiable by positions/nomex flight suits amid fire damage. The fourth (Bollinger) was disputed—Schofield saw none, while the Pararescue Jumper (PJ) claimed a fourth possible figure. No back-end remains; survival vests scattered outside (D - NSA Berkeley Cook 1 Lang Memo.pdf). Nomex suits absent inside the rear fuselage (would be recognizable if incinerated). Quote (p. 12): “I saw three bodies clearly… From my angle, it was only three—definitely no back-enders visible.” Schofield emphasized: “Nomex suits are fire-retardant… If they died on impact, we’d see charred remains or nomex suits inside. We didn’t” (p. 20).

Degradation over 19 years explains scant remains, but egress indicators (door off, open harness buckles, uphill pistols) support High survival indicators for Brandenburg, Cressman, Matejov, Melton. This fuses with Jerry Mooney’s analysis (Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan 11, 1998 & SSC Sworn Testimony): No other losses, intercepts tied to area.

SIGINT Evidence: PAVN Intercepts and NSA Correlations

Declassified NSA SIGINT forms the evidentiary core of this reevaluation, providing real-time documentation of the shootdown, potential capture, and movement of prisoners that aligns closely with the Baron 52 timeline and circumstances. Released under National Security Agency Transparency Case #65888 (approved July 18, 2014), these intercepts were collected by airborne platforms such as the RC-135 Combat Apple, which monitored PAVN communications along the Vietnam coast and Ho Chi Minh Trail. The two intercepts and follow-up message sequence the event from initial engagement to post-incident handling, demonstrating a pattern consistent with the capture of survivors.

The intercepts were analyzed in a preliminary manner immediately after collection, with a subsequent retranslation from the audio recording of the PAVN radio transmission providing greater accuracy. This process, standard for NSA/ASA/USAFSS operations during the era, involved linguists and analysts like Jerry Mooney, who specialized in PAVN Air Defense codes and order of battle (OOB). Mooney’s expertise, as validated in George J. Veith’s 1996 testimony (Dr Jay Veith Testimony .pdf) and July 9, 1996, letter (Dr. Jay Veith Letter on Mooney and NSA Product.pdf), allowed for precise correlation to specific units and locations. In his SSC deposition (Declassified SSC Deposition Jerry Mooney.pdf), Mooney emphasized that the messages were intercepted immediately after the incident, with codes and communication patterns specific to the Saravane area and the 377th Division’s operations. He noted no other U.S. aircraft losses that day, making the link to Baron 52 unequivocal.

- Shootdown Report (USA-29, 150546Z Feb 73): This initial spot report, declassified as part of DOCID: Various (UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER REPORTS SHOOTDOWN OF AN UNIDENTIFIED AIRCRAFT 1983.pdf), captures an unidentified PAVN speaker reporting the downing of an unidentified aircraft at approximately 150545Z Feb 73. The message notes no details on aircraft type, nationality, crew status, or exact location, and is labeled as based on preliminary airborne analysis. This temporal precision matches Baron 52’s last reported contact and the initial AAA engagement (37mm tracers in barrage fire, escalating to radar-directed 57mm or 85mm, as per Wetterhahn’s analysis). The lack of specifics is typical of preliminary reports from forward PAVN units, but the timing—within hours of the crash—indicates real-time PAVN monitoring of Trail airspace, consistent with the 210th AAA Regiment’s radar capabilities.

- Preliminary Captivity Report (2/R0/182-73, 050124Z Feb 73): This multichannel conversation, declassified in DOCID: Various (UNIDENTIFIED MULTICHANNEL CONVERSATION REVEALS CAPTIVITY OF FOUR PILOTS 1983.pdf), reveals: “Group 217 (unid true designator) is holding four pilots captive and the group is requesting orders concerning what to do with them from an unid unit prob subordinate the 559th.” Comments suggest a possible Vinh/BT9 location, based on preliminary analysis. The “four pilots” count precisely aligns with the unrecovered back-end crew (Brandenburg, Cressman, Matejov, Melton), who were electronic warfare specialists often referred to in PAVN comms as “pilots” due to their aerial roles. The “559th” refers to the 559th Transportation Group, the PAVN command responsible for Ho Chi Minh Trail logistics, which extended into southern Laos. This preliminary translation, while noting Vinh as a possible relay point, does not preclude a Laos origin, as wartime signals were frequently relayed through northern hubs like Vinh/BT9 for security.

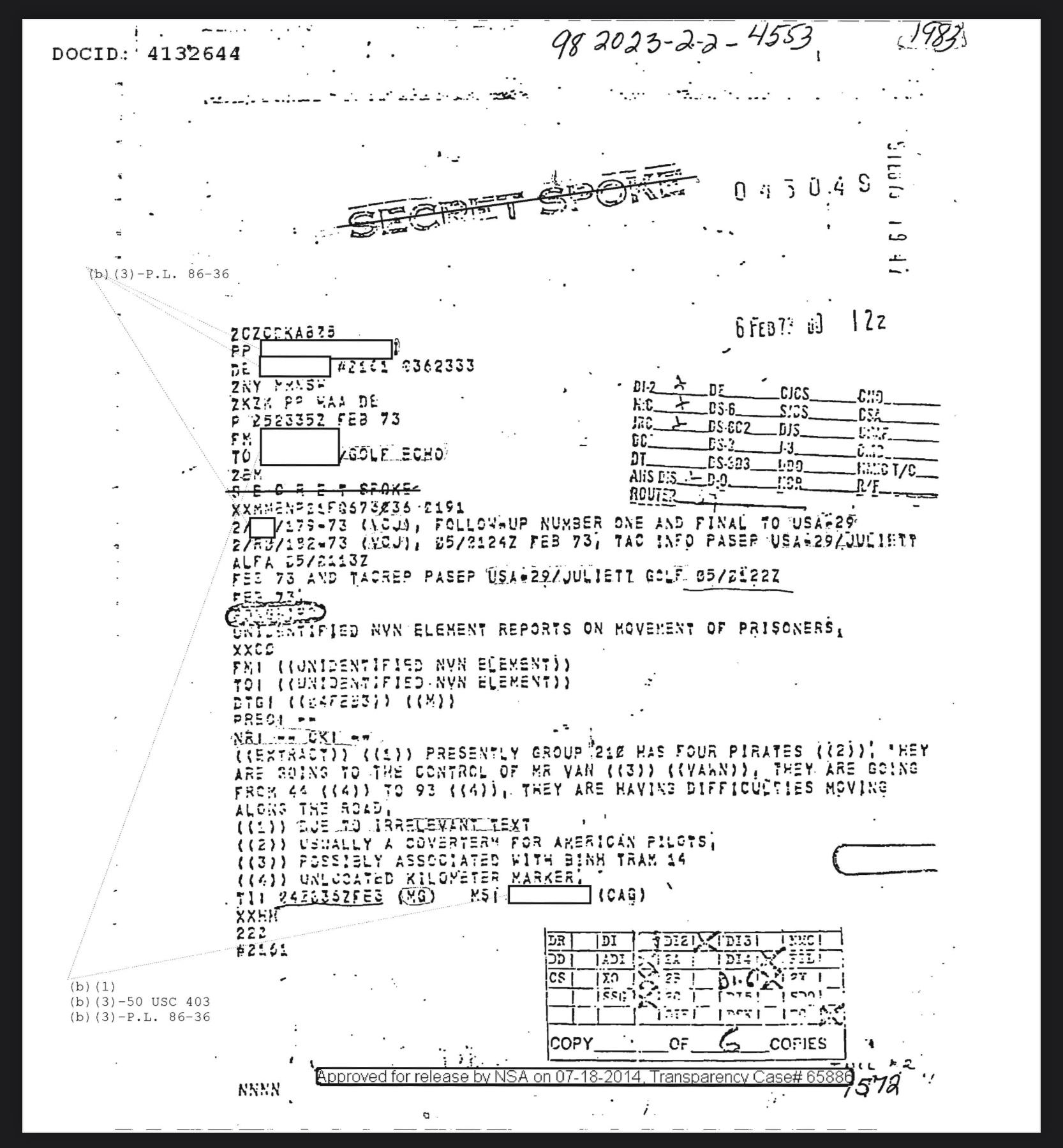

- Retranslated Movement Report (2/R0/186-73, 050630Z Feb 73): The follow-up retranslation from the audio recording, declassified in DOCID: 4132644 (UNIDENTIFIED NVN ELEMENT REPORTS ON MOVEMENT OF PRISONERS, FOLLOW-UP NUMBER ONE AND FINAL 1983.pdf), states: “Unidentified NVN element reports on movement of prisoners. Presently Group 210 has four pirates ((2)), they are going to the control of Mr Van ((3))… from 44 ((4)) to 93 ((4)). They are having difficulties moving along the road.” Footnotes clarify: (2) “Usually a coverterm for American pilots”; (3) “Possibly associated with Binh Tram 14”; (4) “Unlocated kilometer marker.” Labeled “Follow-up Number One and Final,” this version refines the preliminary, shifting from “Group 217/pilots” to “Group 210/pirates,” which enhances accuracy by correcting transcription errors common in real-time airborne intercepts.

The retranslation is considered superior, as it draws from full audio recording of the PAVN radio transmission reviewed at NSA headquarters and forward bases like Nakhon Phanom, Thailand. Group 210 corresponds to the 210th Anti-Aircraft Artillery (AAA) Regiment, a subunit of the 377th Air Defense Division, equipped with 57mm S-60 guns and P-15 “Flat Face” radars—capabilities matching the radar-directed shootdown method described in Wetterhahn’s report. The 210th was deployed in Saravane Province for Trail defense, as confirmed by CIA records and Ho Chi Minh Trail Veterans Association data in Nguyen Hoang’s 2015 memoir (“Early Dry Season 1972 in Southern Laos,” Early dry season 1972 in Southern Laos - Nguyen Hoang - Veteran of Division 48.pdf). “Mr. Van” is identified as Lt. Col. Luong Khanh Van, the 377th’s political officer (1970-1974), responsible for interrogating and transferring high-value prisoners, as per PAVN protocols documented in declassified histories like Military Region 4: The History of the War of National Salvation Against America (1954-1975).

The “four pirates” directly matches the unrecovered back-end crew count, and the translator’s footnote confirmation of “pirates” (“giac”) as a standard PAVN cover term for American airmen distinguishes it from terms like “phi” (bandits) used for local irregulars. The movement from “44 to 93,” interpreted as possible kilometer markers or staging points along the Trail, and “difficulties moving along the road” are consistent with the rugged, mountainous terrain of Saravane Province, where post-crash extraction would involve hidden jungle paths prone to delays.

NSA correlation studies from August 1992, September 1993, and September 1996 (DOCID: 4142094, NSA SIGINT CORRELATION STUDY - POWMIA Master Document 2.pdf), submitted to the Senate Select Committee, explicitly link these intercepts to Baron 52 under REFNO 1983. These studies, based on technical SIGINT analysis including signal frequency, direction-finding triangulation, temporal alignment with the crash timeline, and all-source fusion, affirm the intercepts’ relevance. A 1973 DIA Director level memorandum, referenced in SSC materials, stated there was “reason to believe the four may actually have been captured,” further supporting the correlation.

Jerry Mooney, in his SSC deposition (Declassified SSC Deposition Jerry Mooney.pdf), provided firsthand insight as the NSA analyst who monitored these intercepts in real-time from Room 7A119 at NSA headquarters. Mooney emphasized that the messages were intercepted immediately after the incident, with codes and communication patterns specific to the Saravane area and the 377th Division’s operations. He noted no other U.S. aircraft losses that day, making the link to Baron 52 unequivocal.

These intercepts, collected 5.5 hours post-crash, indicate not only a successful shootdown but also the rapid processing and northward movement of live captives in difficult terrain, consistent with survival and capture scenarios (80% probability). The “final” designation on the retranslation suggests no further PAVN reporting was intercepted, potentially due to secure handling of high-value prisoners or shifts to encrypted or wired communications channels.

Declassified SSC materials, including the January 13, 1993, Covert Operations report (https://irp.fas.org/congress/1993_rpt/15_intel.htm), contextualize these intercepts within broader post-accords intelligence challenges. The report notes SSC’s August 1992 hearing on Baron 52, where Vice Chairman Smith raised concerns over the intercepts occurring the same day as the crash, and DIA’s Destatte disputing correlations as “musings” by Mooney and linking the intercepts to “a friend of a friend’s” ARVN helicopter crews captured near the DMZ. The SSC’s Executive Summary (https://irp.fas.org/congress/1993_rpt/pow-exec.html) reinforces no evidence of living POWs post-1973 but acknowledges unresolved initial captures, recommending enhanced Laos cooperation—relevant to Baron 52’s Laos context.

Rebuttal to DIA Analysis: Challenging the Vinh/Lao Irregulars Theory

The DIA’s analysis of the Baron 52 intercepts, primarily articulated in Robert J. Destatte’s memoranda dated July 17 and 19, 1996, represents a critical point of contention in the case. Destatte, a DIA analyst, concluded that the intercepts had no relation to Baron 52, attributing them instead to the capture and movement of Lao irregulars (“phi” or bandits) near Vinh, North Vietnam; a shift from his 1992 SSC testimony stating it was ARVN helicopter crews near the DMZ. This interpretation, which influenced the DoW’s 1995 KIA closure and the withholding of intelligence from the Military Casualty Review Board, has been subject to extensive scrutiny and rebuttal based on declassified documents, expert testimonies, and cross-source fusions. The following provides a detailed examination of Destatte’s arguments and their flaws, drawing on primary sources to demonstrate why his analysis is untenable and why it necessitates reevaluation.

Destatte’s Core Arguments

In his July 17, 1996, memorandum (“Baron 52–Background Data Concerning 44, 93, and 217,” available via Texas Tech University’s Vietnam Virtual Archive (G.J. Veith Collection) at https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img=/images/1127/11272519024.pdf), Destatte relies heavily on the preliminary intercept translation (“Group 217 is holding four pilots captive”) to posit that the message originated from Route 8 operations in northern panhandle Laos or southern North Vietnam. He interprets “44” and “93” as references to the 44th Infantry Battalion of Ha Tinh Province and the 93rd Border Defense Post at Keo Nua Pass, respectively. Destatte cites PAVN historical texts, such as Military Region 4: The History of the War of National Salvation Against America (1954-1975) (pp. 389-401) and Border Defense Combatants: A Historical Chronicle, Volume 2 (1965-1975) (pp. 270-273), to argue that the intercepts describe mopping-up operations against Lao Government irregulars (Vang Pao’s forces) in campaigns like 972, 872, and 772 during late 1972-early 1973.

The July 19, 1996, follow-up memorandum reinforces this, emphasizing “phi” (bandit) terminology in PAVN reports for Lao captives and dismissing correlations to Baron 52 as speculative. Destatte’s analysis led to the intercepts being deemed unrelated, resulting in their exclusion from the Military Casualty Review Board’s deliberations. This withholding denied the Board—tasked with assessing evidence for status changes—an opportunity to evaluate SIGINT alongside SAR and crash site forensic data, contributing to the approval of a group burial at Arlington National Cemetery and effectively sealing the crew’s fate as KIA, all crew bodies recovered.

Photo: Mary Matejov, mother of Sgt Joseph A. Matejov, is presented with his burial flag.

During the SSC’s August 1992 hearing (as detailed in the January 13, 1993, Covert Operations report, https://irp.fas.org/congress/1993_rpt/15_intel.htm), Destatte testified that the intercepts pertained to South Vietnamese (ARVN) prisoners, attacking NSA analyst Jerry Mooney’s May 1973 informal message correlating the traffic to Baron 52 as “musings.” He claimed to have spoken with SAR team member Ron Schofield, who allegedly discarded survival possibilities, further bolstering DIA’s all-fatality narrative.

Point-by-Point Rebuttal

John Bear’s March 2, 2025, rebuttal (Rebuttal of DIA Analyst Robert J. DeStatte Baron 52.pdf) systematically dismantles Destatte’s framework, supported by declassified NSA studies, veteran testimonies, and PAVN memoirs. The following expands on key flaws:

- Selective Reliance on Preliminary Translation: Destatte prioritizes the less reliable preliminary version (“Group 217/pilots captive”) despite acknowledging the retranslation’s superiority in his own memos. The retranslation (“Group 210 has four pirates… to Mr. Van”) shifts focus to a Laos context, correcting transcription errors common in real-time airborne intercepts (e.g., RC-135 platforms). Bear’s rebuttal notes this as a fundamental methodological error, as NSA protocols emphasize audio-based retranslations for accuracy. SSC investigator Tom Lang’s March 12, 1992, memo (D - Lang Memo Numbers Hearing DIA Files NSA Study.pdf) highlights similar DIA failures to integrate refined NSA SIGINT, leading to misclassifications.

- Misattribution of Unit and Location: Destatte ties “Group 217” to Route 8/7 operations, speculating it moved south to mop up Lao irregulars post-Kham-xom rebellion (December 1972). However, CIA declassified records and PAVN veteran accounts, such as Nguyen Hoang’s 2015 memoir (“Early Dry Season 1972 in Southern Laos,” Early dry season 1972 in Southern Laos - Nguyen Hoang - Veteran of Division 48.pdf), place the 210th Regiment (refined from 217) in Saravane Province by early February 1973, defending Trail segments with radar-directed AAA. Hoang details the 471st Division’s post-rainy season readiness, with subordinate units like the 377th (including 210th) occupying southern Laos. Bear’s rebuttal cites 20+ declassified 1972-1973 intercepts using similar codes for U.S. airmen in Laos, contradicting Vinh localization. Furthermore, Berkeley Cook’s February 13, 1992, SSC interview (D - NSA Berkeley Cook 1 Lang Memo.pdf) recalls analyst doubts on all-dead accounts, supporting a captured context.

- Terminological Inconsistencies: Destatte interprets “pilots” (“phi cong”) and “pirates” (“giac”) as applicable to Lao “phi” (bandits), drawing from PAVN enclosure lists. However, NSA translation footnotes explicitly state “pirates” as “usually a coverterm for American pilots,” distinguishing from “phi” for locals. Bear’s rebuttal analyzes 1972-1973 intercepts showing “giac” reserved for U.S. airmen, while “phi” denoted irregulars in ground ops. George J. Veith’s compilation (“The Mooney Documents.pdf,” TheMooneyDocuments.pdf) includes a 1972 execution incident involving the 377th Division, where similar terms described U.S. captives, paralleling Baron 52’s potential fate.

- Prisoner Handling Discrepancies: Destatte claims the intercepts describe routine Lao captive movements, but “Mr. Van” (Luong Khanh Van) was the 377th’s political officer, tasked with high-value POWs for interrogation/transfer (per PAVN protocols in). Bear notes this role is inconsistent with low-priority Lao handling, who were processed locally to Pathet Lao reeducation camps. Veith’s 1996 testimony (Dr Jay Veith Testimony .pdf) critiques DIA’s non-use of NSA product, citing Mooney’s OOB expertise showing 377th’s involvement in prior U.S. aircrew captures.

- Signal Attribution Errors: Vinh/BT9 indicators, per Destatte, tie to northern ops, but NSA technical notes explain them as forwards from Laos to secure Vinh hubs. NSA analyst Jerry Kelly’s February 24, 1992, SSC interview (D - Tom Lang Memo NSA Kelly.pdf) on post-1975 purges notes - lost all source working aids could have clarified this. Bear’s rebuttal, fused with Mooney’s deposition, argues temporal/spatial fit (5.5 hours post-crash, Saravane triangulation) overrides Vinh speculation.

- Misrepresentation of SAR Evidence: In the 1992 SSC hearing, Destatte claimed Schofield “discarded” survival possibilities. However, Schofield’s deposition (LOC frd/pwmia/295/91954.pdf) refutes this: He confirmed only three front-end remains, disputed fourth, and noted egress indicators for the back-end crew (door off, no nomex bodies), estimating 70% back-end survival. Schofield accused Destatte of twisting his words to fit DIA’s narrative (p. 28: “He [Destatte] called me… twisted what I said”). This misrepresentation, per Bear, underscores DIA bias.

Integration of Sedgwick Tourison’s Memorandum and Blocked Intelligence

Sedgwick Tourison’s December 17, 1991, memo (Copy of 7. 91 Tourison Memo On Baron 52.pdf, 20 pages), prepared as an SSC investigator with expertise as an Army Security Agency (ASA) veteran and retired DIA POW/MIA analyst, provides critical insight into the rushed KIA designation and intelligence obstructions surrounding Baron 52. Tourison, who led SSC probes into “numbers” discrepancies, notes the absence of a single reliable U.S. record of wartime captures, identifying two unaccounted-for MIA “lists”—only one official—with DIA providing the non-official version to the Committee.

Specifically on Baron 52, Tourison highlights the U.S. Air Force’s KIA-BNR report three weeks post-loss (late February 1973), despite “no compelling evidence of death” and procedures inconsistent with normal casualty investigations. He reveals U.S. military intelligence resources in Laos and Thailand—capable of determining crew fates (e.g., CIA trained Hmong scouts, Thai intel)—were “actively prevented” from deployment by the CIA Station in Vientiane. This block, potentially to safeguard post-accords diplomacy or conceal ongoing covert ops (e.g., future ARDF missions, CIA backed indigenous road watch teams), limited follow-up and contributed to premature closure.

Tourison’s findings, based on DoD casualty history and a planned DIA meeting for data, underscore “two sets of books” impacts on POW/MIA resolution, suggesting systemic failures in intelligence correlation led to misclassifications. This fuses with Schofield’s deposition (frd/pwmia/295/91954.pdf, p. 28: frustration over withheld intel) and SSC Covert Operations report (https://irp.fas.org/congress/1993_rpt/15_intel.htm), noting CIA opposition to agent ops for POW intel despite priorities. The block aligns with 1981 Laos incursion debates, where similar sensitivities hindered left behind captured American POW confirmation.

Destatte’s unrelated conclusion withheld the intercepts from the Military Casualty Review Board, denying the Board to make an informed assessment before approving Arlington group burial—sealing the fate of all Baron 52’s crew as KIA.

PAVN Order of Battle and Actionable Leads

The People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) order of battle (OOB) for the relevant units provides a structured framework for understanding the operational environment surrounding the Baron 52 shootdown and offers actionable leads for further investigation. During 1972-1973, the PAVN 471st Division, headquartered in Nam Bac, Laos, served as the overarching regional command for Trail defense operations in southern Laos, overseeing subordinate units tasked with anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) and logistics protection. Formed in the mid-1960s as part of PAVN’s expansion into Laos to secure the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the 471st had an estimated strength of 3,000-5,000 personnel, including infantry, engineering, and air defense elements. Its role was multifaceted: logistical, securing supply lines, countering U.S. reconnaissance, and coordinating with Pathet Lao forces against Royal Lao Government irregulars.

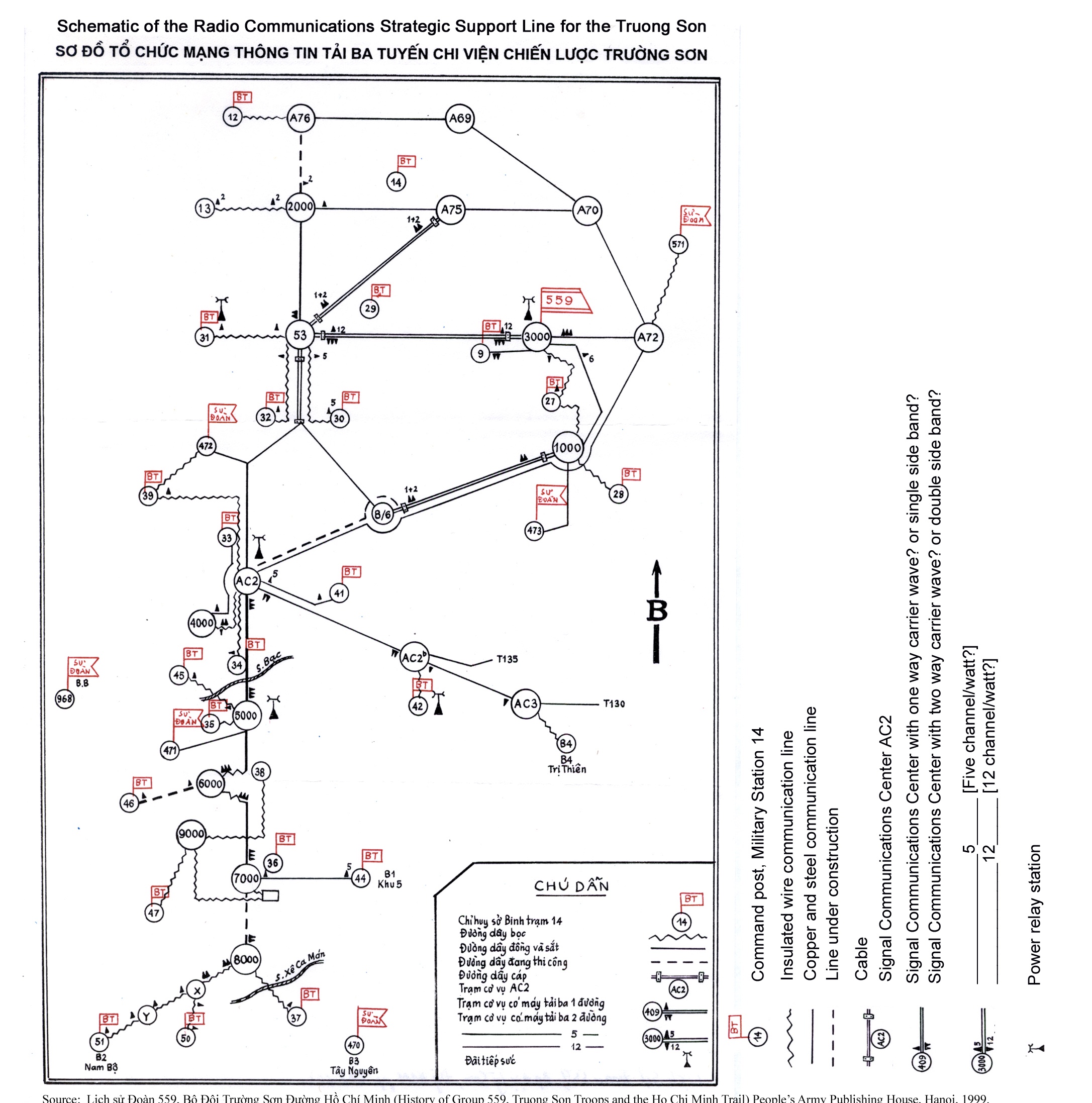

Nguyen Hoang’s 2015 memoir (“Early Dry Season 1972 in Southern Laos,” Early dry season 1972 in Southern Laos - Nguyen Hoang - Veteran of Division 48.pdf) details the 471st’s post-rainy season preparations, emphasizing its readiness to resume operations after the 1972 monsoon. Hoang, a veteran of the 471st (misnoted as 471 in some translations, but contextually the same), describes the division’s management of vertical routes (e.g., 128, 22, 24, 17) and crossroads like B46, with stations such as (Binh Trams - logistical units) BT35, BT44, BT36, BT38, BT46, and BT47 reinforcing tunnels and roads. The memoir highlights the division’s integration of wired/wireless communications from command posts to small units, facilitating rapid reporting—as seen in the February 5 intercepts. Hoang notes the 593rd Anti-Aircraft Regiment (a sibling unit to the 210th) equipped with 23mm to 57mm caliber weapons for low- and high-altitude threats, underscoring the 471st’s air defense posture against U.S. aircraft like AC-130s and reconnaissance aircraft like Baron 52.

The 377th Air Defense Division, a key subordinate under the 471st, was formed in 1966 with approximately 1,200 personnel and specialized in protecting logistics routes. Equipped with S-60 57mm guns, ZU-23 23mm autocannons, and P-15 “Flat Face” radars, the 377th was deployed in Saravane to counter U.S. reconnaissance flights, as confirmed by CIA declassified intelligence and Hoang’s account of post-rainy reinforcements. The division’s role in the “early dry season 1972” included arranging underground positions to combat AC-130 gunships and B-52 strikes, with radar-directed AAA matching Baron 52’s reported engagement.

The 210th AAA Regiment, a direct subunit of the 377th, was positioned 5-10 km south and northeast of the crash site and equipped for radar-guided fire, aligning with the intercepts’ “Group 210” reference. With ~300-400 personnel, the 210th focused on Trail segment defense, shifting south by mid-February 1973 per CIA reporting.

Hoang’s memoir also provides broader OOB insights: The 471st integrated the 59th Infantry Regiment (newly mobilized for combat readiness) and affiliated battalions, occupying southern Laos and western Quang Nam with nearly 1,000 km of dirt roads cleared by engineers. Communication systems connected command to traffic control stations, enabling the rapid intercept reporting.

This OOB structure, fused with intercepts, implicates these units in the shootdown and handling. Actionable leads for VNOSMP interviews include surviving veterans, accessible through Vietnamese veteran associations (e.g., Ho Chi Minh Trail Veterans Association), where many 1930s-1940s-born officers remain active.

Key personnel:

- Lt. Col. Luong Khanh Van: 377th political officer (1970-1974), handled POW interrogation/transfer; likely decided post-crash actions.

- Lt. Col. Nguyen Huu Ich: 377th commander, oversaw February 1973 ops.

- Lt. Col. Doan Thuan: 377th deputy commander, coordinated AAA.

- Lt. Col. Ho Quang Trung: 471st commander, directed regional strategy.

- Lt. Col. Nguyen Van Lan: 471st deputy, managed regional logistics.

- Lt Col. Hoàng Đình Cựu: 210th Commander, led the unit responsible for the shootdown and initial capture.

- Lt. Col. Trần Hiền Đệ: 210th political officer, supported potential prisoner custody and movement.

VNOSMP, leveraging U.S.-Vietnam ties, can access these veterans for insights on shootdown, captives, and fates—essential due to U.S. intel gaps.

Recommendations: Path Forward Through VNOSMP Engagement

The evidence supports a High probability of initial survival and capture for the four back-end crew members, underscoring systemic flaws in the U.S. accounting process, such as intelligence compartmentalization, post-accords diplomatic pressures, and underutilization of SIGINT. Notably, in a March 1996 letter to Sen. Bob Smith, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense James W. Wold committed that the Joint Task Force-Full Accounting (JTF-FA) would request the Vietnamese government to identify three Vietnamese officials who visited the Baron 52 crash site shortly after the incident for the purpose of conducting interviews; however, the DoD has never followed through on this promise, further exemplifying these accountability gaps. To address these issues and provide closure, the DoW must reevaluate the case and allocate resources for collaboration with the Vietnamese Office for Seeking Missing Persons (VNOSMP) to interview surviving veterans from the 210th, 377th, and 471st units. This non-invasive approach leverages strengthened U.S.-Vietnam relations and aligns with the nation’s commitment to the “fullest possible accounting.”

To advance resolution, AMAG provides the following clear and detailed recommendations:

- Formal Case Reevaluation by DPAA: DPAA should immediately reclassify the four back-end crew members (Brandenburg, Cressman, Matejov, Melton) as Missing in Action (MIA) pending a comprehensive review. This should incorporate NSA correlation studies (1992-1996), Wetterhahn’s survivability assessment, Schofield’s SAR testimony, and intercepts, addressing Tourison’s SSC-noted “two sets of books” discrepancies.

- Resource Allocation for VNOSMP Collaboration: The DoW should allocate funding and diplomatic support for joint U.S.-Vietnam efforts through VNOSMP to conduct targeted interviews with surviving PAVN veterans from the 210th, 377th, and 471st units. Prioritize Lt. Col. Luong Khanh Van (or associates) for details on prisoner handling, given his intercepts role. Interviews should focus on: shootdown circumstances, post-crash recovery, captive movements (“44 to 93”), and fates. These interviews can also support other unresolved MIA cases in southern Laos. Due to veterans’ advanced age (many 80s-90s), interviews must be conducted urgently—within 3 to 6 months to preserve testimonies.

- Expedited Declassification and FOIA Processing: DoW and NSA accelerated release of queued FOIA materials (e.g., NSA Case 120305A PAVN audio/transcripts and DIA 180-2023 - Interagency POW/MIA Intelligence Ad-Hoc Committee documents) via congressional intelligence oversight committees. Declassify remaining NSA, DIA and CIA files on REFNO 1983 (Baron 52) to enable a transparent independent evaluation.

- Public Transparency and Oversight: Declassification of all POW/MIA documents and materials still held by the Agencies in their archives.

These recommendations, respecting family sensitivities, fulfill ethical and legal mandates for accounting while advancing broader MIA resolutions.

Continuation: Unveiling the Tang Cat Km 44 Connection

For additional insights into the “Km 44 to 93” references in the PAVN intercepts and their geographical ties to the Baron 52 crash location and the Tang Cat area along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which further strengthens the evidence for crew survival and capture, please read our follow-up report: “Unveiling the Tang Cat Km 44 Connection: Fresh Insights into Baron 52’s Crew Survival and Capture” available at https://www.storiesofsacrifice.org/blog/unveiling-the-tang-cat-km-44-connection-fresh-insights-into-baron-52s-crew-survival-and-capture/. This continuation builds directly on the analysis presented here, providing new declassified leads and updated recommendations for investigation.

Media References:

- Atherton, H. (2023, January 27). 50 years later, peace treaty that was supposed to end Vietnam War still haunts my family. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/voices/2023/01/21/vietnam-war-paris-peace-accords-remember-baron-52/11021128002/

- McLaughlin, K. (2025, February 2). What happened to the crew of a U.S. spy plane shot down by North Vietnamese? The War Horse. https://thewarhorse.org/what-happened-to-crew-of-us-spy-plane-shot-down-by-north-vietnamese/

- Wetterhahn, R. (2023, February). ‘All of Them Needed to be Dead’: An Air Force surveillance plane crashed in Laos the week after the signing of the Paris Peace Accords. The fate of the crew still is unknown. VFW Magazine. https://www.qgdigitalpublishing.com/publication/?i=773598&p=30&view=issueViewer

- Lodewyk, G. (2025, June 12). Story man seeks truth about brother’s Vietnam War disappearance. The Sheridan Press. https://www.thesheridanpress.com/news/local/story-man-seeks-truth-about-brother-s-vietnam-war-disappearance/article_844ea4f8-549d-4e27-8d8f-83eea5b84b42.html

- Bear, J. (2023). Baron 52 MIA Mystery Docu Series Podcast [Audio & Video podcast series]. Stories of Sacrifice. https://www.storiesofsacrifice.org/categories/baron-52/

- Bear, J. (2025, July). Baron 52: A Family’s Half-Century Fight for Truth Against Bureaucracy and Greed. Stories of Sacrifice. https://www.storiesofsacrifice.org/blog/baron-52-a-familys-half-century-fight/

References:

- Wetterhahn, R. F. (2016). An Analysis of The Crash Sequence EC-47Q Baron-52 February 5, 1973. (Crash Analysis & Evidence of Survival.pdf) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1y2Gn_3qlV1qiie-49FfrVT1qYo5i2CW6/view?usp=drivesdk

- NSA. (2008). NSA SIGINT CORRELATION STUDY - POWMIA Master Document 2. DOCID: 4142094. (NSA SIGINT CORRELATION STUDY - POWMIA Master Document 2.pdf) NSA Link to all three drafts. See REFNO 1983 Baron 52 https://www.nsa.gov/Helpful-Links/NSA-FOIA/Declassification-Transparency-Initiatives/Historical-Releases/Vietnam-Powmia-Documents/smdsearch14709/Study/

- Schofield, R. (1992). SSC Deposition. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/476595

- Bear, J. (2025). Rebuttal to Robert J. Destatte’s Analysis. (Rebuttal of DIA Analyst Robert J. DeStatte Baron 52.pdf) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bgxDl7dXVSAfwSEIIndUW3uKvQxxBVAo/view?usp=drivesdk

- NSA. (2025). FOIA Response Case 120305A. (NSA FIOA - 120305A BEAR LTR.pdf) https://drive.google.com/file/d/14HEcdhkS7tPy8aZUilUW05-qosXX1Xd5/view?usp=drivesdk

- NSA. (1973). Unidentified Speaker Reports Shootdown. DOCID: Various. (UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER REPORTS SHOOTDOWN OF AN UNIDENTIFIED AIRCRAFT 1983.pdf) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1e-8An2o1uDgcrUOK1Aq7ZMMHAiRadbSW/view?usp=drivesdk

- (UNIDENTIFIED NVN ELEMENT REPORTS ON MOVEMENT OF PRISONERS, FOLLOW-UP NUMBER ONE AND FINAL 1983.pdf) https://media.defense.gov/2021/Aug/10/2002828270/-1/-1/0/UNIDENTIFIED%20NVN%20ELEMENT%20REPORTS%20ON%20MOVEMENT%20OF%20PRISONERS,%20FOLLOW-UP%20NUMBER%20ONE%20AND%20FINAL%201983.PDF

- NSA. (1973). Unidentified Multichannel Conversation Reveals Captivity. DOCID: Various. (UNIDENTIFIED MULTICHANNEL CONVERSATION REVEALS CAPTIVITY OF FOUR PILOTS 1983.pdf) https://media.defense.gov/2021/Aug/10/2002828258/-1/-1/0/UNIDENTIFIED%20MULTICHANNEL%20CONVERSATION%20REVEALS%20CAPTIVITY%20OF%20FOUR%20PILOTS%201983.PDF

- Hoang, N. (2015). Early Dry Season 1972 in Southern Laos. (Early dry season 1972 in Southern Laos - Nguyen Hoang - Veteran of Division 48.pdf) http://hoitruongson.vn/tin-tuc/2121_10933/-dau-mua-kho-1972-o-nam-lao-nguyen-hoang-ccb-su-doan-471.htm

- Tourison, S. D. (1991). Unraveling the POW/MIA Numbers: A Status Report. (Copy of 7. 91 Tourison Memo On Baron 52.pdf) https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img=/images/286/2860110018.pdf

- Lang, T. (1992). Outline for “Closed” Hearing. (D - Lang Memo Numbers Hearing DIA Files NSA Study.pdf) https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img=/images/367/3671508030.pdf

- Lang, T. (1992). Interview with Berkeley Cook. (D - NSA Berkeley Cook 1 Lang Memo.pdf) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1uH0-cUwankV_mJ6Gnu3LeK0-6iPOxfTw/view?usp=drivesdk

- Lang, T. (1992). Interview with Jerry Kelly. (D - Tom Lang Memo NSA Kelly.pdf) https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img=/images/367/3671508026.pdf

- Veith, G. J. (1996). Testimony before House Subcommittee. (Dr Jay Veith Testimony .pdf) https://ia800605.us.archive.org/15/items/accountingforpow00unit/accountingforpow00unit.pdf & https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img=/images/367/3671511011.pdf

- Veith, G. J. (1996). Letter to Richard K. Childress. (Dr. Jay Veith Letter on Mooney and NSA Product.pdf) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1i2NymfKjzw6PtRKZBeKyhKuRx6SrgdEW/view?usp=drivesdk

- Lubrano, A. (1998). The Untold Story of Baron 52. Philadelphia Inquirer. (Phillyinquirearticle.pdf.pdf) https://archive.ec47.com/untold52.htm

- Veith, G. J. (1995). The Mooney Documents. (TheMooneyDocuments.pdf) https://www.prisoner-of-war.com/TheMooneyDocuments.pdf

- SSC. (1993). Covert Operations Report. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1993_rpt/15_intel.html https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img=/images/367/3671508029.pdf

- SSC. (1993). Executive Summary Report. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1993_rpt/pow-exec.html

- Wold, James W. “Letter to Senator Robert C. Smith Regarding the Baron 52 Incident.” Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense, International Security Affairs, March 22, 1996. Virtual Vietnam Archive, Texas Tech University. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img=/images/367/3671506003.pdf

- DIA. (2023). Interim Response to Matejov J. FOIA Request Case 00180-2023. (FOIA-00180-2023.pdf) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1fDc9MQcoR292AJrUHbub_BewPXhV05Gw/view?usp=drivesdk Video Referenced in FOIA: https://youtu.be/LdzQnXGgIR4?si=aOcZrW7VMtrydPSN