Echoes from the Fishhook: The Phantom Capture of Cobra 84 and the Enduring Shadow of REFNO 1619

By John Bear, Chief of Investigative Research, Asymmetric MIA Accounting Group (AMAG)

In the sweltering haze of May 1970, as the Vietnam War’s secret underbelly churned in the tri-border wilderness where Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia collided, an F-4D Phantom II streaked low over the jagged ridges of northeast Cambodia’s Fishhook salient. Call sign: Cobra 84. Crew: Captain Alan R. Trent, the steady-handed pilot from the 480th Tactical Fighter Squadron, and First Lieutenant Eric James “Rick” Huberth, the 24-year-old systems officer whose California roots masked a quiet fire for flight. Their mission was routine yet lethal—close air support to pulverize a PAVN bridge and a secondary target, a PAVN base camp in the heart of enemy logistics country, part of the covert Operation Menu bombings that would soon ignite Cambodia’s descent into chaos.

At approximately 1,500 feet, ground fire erupted. Rifle rounds—likely from an AK-47 or DShK—stitched the humid air. Trent yanked back on the stick for a late pull-off, but the Phantom, tail number 65-0607, betrayed them. It slammed into a hilltop, bounced across a second, and augered into the third, erupting in a fireball that lit the jungle canopy like a funeral pyre. No parachutes bloomed. No beacons beeped. Just silence, broken by the distant chatter of PAVN radios.

That was May 13, 1970. REFNO 1619. Fifty-five years later, Trent and Huberth remain unaccounted for—two ghosts in a war that swallowed 1,602 Americans whole. But this isn’t just another MIA tale of faded dog tags and memorial walls. It’s a story laced with intercepted whispers of capture, a pith helmet etched with a name that could unlock secrets, and PAVN units whose engineers and infantry danced in the shadows of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. At its core lies an unresolved enigma: NSA signals intelligence suggesting one American was taken alive. A phantom capture, buried in classified files, dismissed by some, yet haunting enough to drive a MACV SOG Green Beret back to the jungle at age 70.

As a research representative for families like the Huberths—through my work with the Asymmetric MIA Accounting Group (AMAG) and the Stories of Sacrifice podcast—I’ve sifted through FOIA releases, DPAA case summaries, and veteran testimonies. This post weaves it all together: the crash’s chaos, the SOG Bright Light’s desperate probe, the SIGINT’s cryptic echo, the PAVN 470th Division’s iron grip on the Fishhook, and the helmet’s tantalizing clue. It’s a deep dive into why Cobra 84 refuses to fade—and why we must keep digging.

The Shadow War in the Fishhook: A Tri-Border Inferno

To grasp Cobra 84’s fate, you must first map the madness of the tri-border. In early 1970, the region—where Vietnam’s Central Highlands bled into Laos’ Attapeu Province and Cambodia’s Ratanakiri—was a PAVN fortress. The Fishhook salient, a dagger of neutral Cambodian soil jutting 40 miles into South Vietnam, was the Ho Chi Minh Trail’s western flank. Here, 559 Trường Sơn Command funneled rice, ammo, and men southward, shielded by triple-canopy jungle and karst ridges rising to 2,500 feet.

The PAVN’s 470th Division, freshly forged on April 15, 1970, at Nậm Pa forest in southern Laos, claimed this turf as its cradle. Commanded by officers like Lê Xuân Bá, the division blended infantry regiments (e.g., Trung đoàn 4 Ngô Gia Tự) with engineer battalions tasked with road-building and camp fortification. By May, its Trung đoàn Công binh 4 (4th Engineer Regiment) was entrenched in the Fishhook, opening 885 km of new trails and repairing 3,120 km more—vital arteries from Phi Hà (the tripoint junction) to Kratrê Province. These weren’t mere sappers; they were dual-threat warriors, wielding AKs and SA-7s against low-level intruders like F-4s.

Cambodia’s Lon Nol coup in March 1970 had upended the status quo, but PAVN forces—some 40,000 strong—dug in deeper. Binh Trạm 50, 51, and 53 PAVN logistics stations dotted Ratanakiri, securing Sê-rê-pốk River crossings and truck parks. The 470th’s AOR stretched from Plây Khốc to Tà Ngâu, encompassing grid 48P YA 646 995—the crash site on low ridge at 627 meters amid karst gullies.

Cobra 84’s target: a bridge at YA 513 936, ~2 km west. Departing Phu Cat Air Base, the flight of two Phantoms dove through monsoon haze. The wingman saw Trent’s abrupt maneuver, then the fireball. Forward Air Controller (FAC) reported: “No chutes, no beepers.” But in the camp below—hooches on stilts, bamboo-fenced cemetery, animal pens—PAVN troops scrambled. Fires were doused with fresh dirt with valuable wreckage salvaged. And radios crackled.

This was no random hit. The 470th’s engineers, per Vietnamese histories on qdnd.vn, were “hitting the enemy” with rifle fire against low-fliers. Feats like Bùi Xuân Nơ downing an F-4 with nine machine-gun rounds in the 1969–70 dry season underscore their marksmanship. Cobra 84 likely fell to Trung đoàn Công binh 4 patrols—small arms stitching the Phantom’s belly at 500 knots.

The crash’s severity? Total disintegration, per SOG. But the three-hill path—bounce, plow, auger—hints at fleeting survival windows. Enter the SIGINT.

The Phantom Intercepts: SIGINT’s Unresolved Whisper

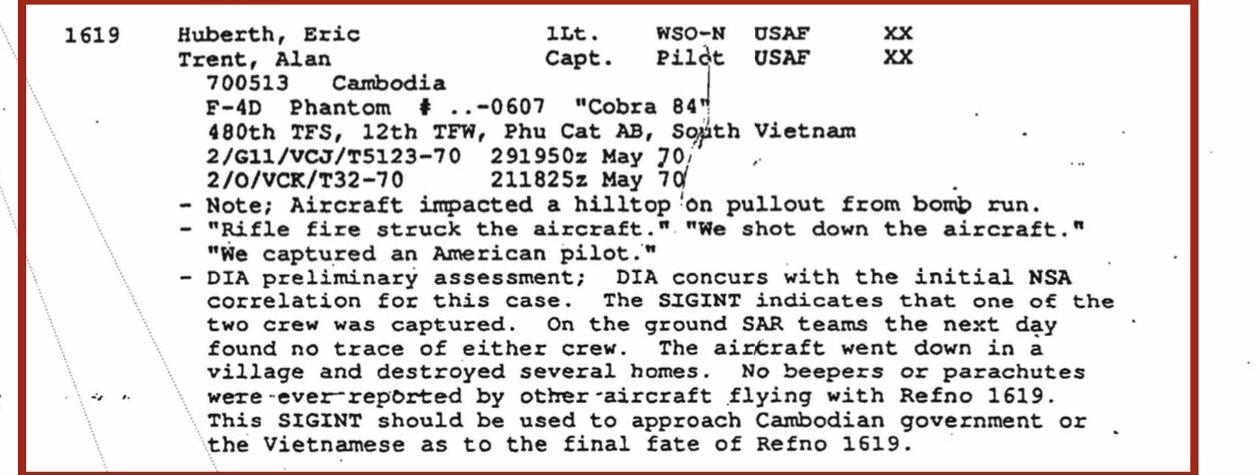

In the classified ether of May 1970, NSA intercepts pierced the jungle veil, capturing PAVN radio traffic that would haunt REFNO 1619 for decades. Two key messages, declassified in 2014, emerged: the first detailing the shootdown of an F-4 by rifle fire, the second reporting the capture of an American pilot. The intercepts were initially correlated directly to Cobra 84’s loss.

The shootdown intercept painted a vivid scene: Ground fire striking the aircraft as it pulled off the target, leading to an immediate impact. But the capture report added a layer of mystery—“We captured an American pilot,” with details of the plane hitting a village, destroying homes, and no parachutes or beepers reported. DIA’s preliminary assessment concurred with NSA, noting the SIGINT indicated one of the two crew was taken alive. Ground SAR the next day found no trace, yet the intercepts suggested quick enemy action amid the wreckage.

For years, these signals fueled hope and frustration. Senate Select Committee hearings revealed the info was withheld until at least the 1990s Senate Select Committee investigation. Yet, DPAA’s 2023 Case Summary deems them “inconsistent”—the “flew away in flames” phrase clashes with eyewitness immediate impact, and shadows/smoke obscured views. No raw transcripts or voice tapes have been fully declassified.

SOG team member Jim Shorten’s 2002 IIR speculation echoes the intercepts: Crew possibly “thrown from aircraft… taken by Vietnamese.” The boot - recovered but chain of custody lost? Perhaps evidence of brief survival. In Ratanakiri’s PAVN camps, quick-grabs were routine—PAVN units hauling pilots to V211 Hospital or northward. Unresolved, this SIGINT isn’t dismissed; it’s a persistent whisper, urging re-analysis amid 470th oral histories.

The helmet ties it tighter.

The Helmet of Lê Đình Sâu: A Name from the Ashes

The morning of May 14, 1970, dawned gray and tense over the crash ridge. A MACV SOG recon team—RT Delaware—dropped from two Huey helicopters using rope ladders. The team leader was Jim Shorten, a Green Beret who spoke fluent Vietnamese. With him were SSG Homer Hungerford, five Montagnard scouts, and a mission: find the two missing pilots of Cobra 84.

The landing zone was “hot.” Enemy soldiers already knew they were coming.

What the Team Saw as They Moved South

As per Shorten’s 2002 statement to investigators:

“(A) The witness (Jim Shorten) along with another U.S. soldier, SSG Homer Hungerford, and five Montagnard team members (names not recalled), were sent to the case 1619 crash site to rescue or retrieve the aircrew. Although the case aircraft crashed on May 13, 1970, the Bright Light team was not inserted until 14 May 1970. The team inserted light, the witness and three Montagnard soldiers inserted first followed by SSG Hungerford and the two remaining Montagnard soldiers. The team inserted at the point of impact of the 1619 aircraft at 48P YA 6465 9990. The team moved south following the path of the aircraft after impact. The team sighted enemy soldiers in the area, but did not exchange fire. The witness checked an enemy trench to the west which paralleled his route of travel. To the east of the team, there was a house on stilts; on the side of the house was a fenced in area, which was a cemetery. There were six or seven graves which were not recent, as evidenced by an accumulation of debris on them, and each was marked by stones with names written faintly on the stone. The witness and the rest of the team continued moving south and could discern an enemy truck park at the bottom of the hill along a road (YA 647 997). The team crossed the low ground and started up the next hill (YA 647 996). The entire low ground approximately one third of the way up the hill, the team gathered any wreckage which could help to identify the aircraft, but the witness does not remember any aircrew related items or life support equipment being present.

(B) While moving up hill, the witness heard the enemy moving around in the area. At the top of the hill, he saw a small village of five to six lightweight hooches (huts) on the ground with woven bamboo used as camouflage over the top. There was an unexploded bomb in the village and scattered debris which looked like it had recently vacated. To the west of the village was a unit (PAVN). With the direction of a Peoples Army of Vietnam (PAVN) engineer unit being 12 o’clock, the village of hooches was at approximately 2:30 hours and the enemy was moving up hill from the 9 o’clock position. At this time the witness was a quarter to a third of the way up the next finger and could see what he believed to be the case 1619 F-4 aircraft fuselage. It was 100 meters, at the 12 o’clock position, abutted against a parallel to the slope of the hill. Due to bad weather, the enemy moving in, and the mission was aborted by the TAC prior making it to the fuselage and the cockpit area.

(C) After returning from the mission, SSG Hungerford related to the witness that one of the Montagnards found a boot. Later Colonel McCowan, the command control and communications commander commented that a boot with remains was brought back to the base camp. Since remains were not seen in the aircraft wreckage debris field, the witness assumed the aircrew either: ejected on impact, were thrown from the aircraft when it impacted the slope of the hill, or remained in the cockpit area and were taken away by the Vietnamese. The witness was not satisfied with the lack of mission success and knowledge or the final status of the aircrew.”

The One Thing They Brought Back

Among the debris, the team recovered a North Vietnamese pith helmet. On the inside was handwritten:

Le Dinh Sau HT 6321

Who Was Lê Đình Sâu?

The name was jotted down in the field as “Le Dinh Sau.” With proper Vietnamese accents, it’s Lê Đình Sâu—pronounced like Lay – Jeeng – Sów.

He was probably a logistics soldier or engineer in the 470th Division, hailing from areas like Đắk Lắk Province. Was HT 6321 his military ID number or a temporary military unit ID?

Modern searches in Vietnam’s veteran databases (like Hội Cựu Chiến Binh) come up empty for 1970 matches. But the Vietnam Office for Seeking Missing Persons (VNOSMP) offers hope: A query for “Lê Đình Sâu HT 6321, B3 Front, May 1970” might track him down—or his associates.

If found, he could reveal:

- Did your unit pull a survivor from the burning wreck?

- Were any American remains hastily buried in the nearby cemetery the SOG team spotted?

Why This Helmet Still Echoes Today

This wasn’t just stray gear. It belonged to a soldier right in the camp where Cobra 84 smashed down. The 4th Engineer Regiment built hidden roads, guarded supply lines, and fired at incoming jets. Their pith helmets—lightweight for the steamy jungle, often marked with personal touches—were everyday items.

Vietnamese military histories celebrate the 470th for carving out the “strategic rear” in the Fishhook in 1970. They clashed in hundreds of skirmishes and boasted about routine takedowns of aircraft.

This helmet is no mere relic. It’s a tangible link to the troops on the ground that fateful day—and possibly the last to witness Trent or Huberth’s final moments. It’s a trail of clues pointing straight to the mystery of the phantom capture.

Jim Shorten’s Reckoning: A Green Beret’s Jungle Ghosts

No one embodies the unyielding pull of an unfinished mission like Jim Shorten—a MACV-SOG legend who led Recon Team (RT) Delaware as its One-Zero. Before SOG, Shorten was a U.S. Navy sailor who switched to Army Special Forces, even turning down a promotion to E-8 to deploy faster. He craved the high-stakes world of jumping from helicopters into hostile territory, bonding with Air Force Para Rescue Jumpers along the way. His second Vietnam tour, an 18-month odyssey with SOG out of Command and Control Central (CCC) in Kontum, saw him bunk with the irrepressible John Plaster and master the Vietnamese language to communicate seamlessly with his Montagnard “little people.”

But it’s the Bright Light mission on May 14, 1970—a frantic rescue attempt for Cobra 84’s crew—that haunts him most. As detailed in the gripping seven-part SOFREP series by John Stryker Meyer (former SOG One-Zero and Chapter 78 President), Shorten’s team inserted into a hornet’s nest near the Cambodia-Laos border. The F-4 Phantom had been hit by ground fire during a low-altitude bombing run, bouncing off the first of three hilltops before plowing into the second and augering into the third. Shorten’s squad got close to the wreckage but was pinned by ~1,500 converging PAVN troops. Extraction came under fire: The first Huey lifted off smoothly, but the second clipped a tree, shearing a foot from each rotor blade. Miraculously, the battered bird hauled the remaining four men—Shorten included—through freezing winds for a 40-minute limp back to Dak To.

Waiting at base were the surviving Phantom crew, eyes desperate for news. Shorten had none. “This rode heavily on Jim’s mind,” Meyer writes, a weight that grew over decades.

The 2002 Return: A Self-Funded Quest into the Unknown

By 2002, 32 years after the failed Bright Light, Shorten couldn’t shake the ghosts. Previous U.S. recovery efforts—Joint Task Force-Full Accounting (JTF-FA) digs in the 1990s—had unearthed life-support gear but no remains, hampered by bandits and rebels. Determined to go further, Shorten self-funded a $35,000 expedition, hiring locals and trekking where official teams couldn’t.

Preparation and the Road In

Landing in Phnom Penh on February 20, Shorten linked up with old teammate Harlow Short and son Matthew (ex-ODA-502). He briefed JTF-FA on prior intel, learning 1993 searches yielded crew items but hit dead ends after 10-hour hunts. A Cambodian Ranger warned of armed threats and a brutal 64-mile mountain trek through bamboo-choked jungle. Undeterred, Shorten assembled five Rangers and set out—23 days, 100 miles total.

The hike was hellish. Dense undergrowth hid the Ho Chi Minh Trail remnants; on the final push, they crossed the very bridge Cobra 84 targeted, spotting a gutted communications bunker with dangling wires and antennae.

Challenges on the Ground

Day two at the site: Scavengers had stripped the jet to bones—heavy metal hulks only, no lightweight clues. A metal detector beeped uselessly amid shell casings from old firefights. The 5–6 inches of decayed vegetation buried everything; bamboo slashed like knives.

Night two brought terror. Renegade police/army—bandits in uniform—held them at gunpoint, demanding their mission. The lead Ranger, son of a province chief, talked them down, but the warning rang clear: “Leave or die.” Shorten, unarmed and outnumbered, felt the void of his 1970 RT Delaware brothers. “I felt as though I’ve failed the crew of Cobra 84 and their families,” he later told Meyer.

Findings and Frustration

They scoured the hill, and a troop regrouping camp. Small jet fragments surfaced—later gifted to families for solace—but no human remains. The jungle had reclaimed it all.

Emotional Toll

Back in Arizona, flashbacks intensified: NVA advancing, the jet, dangling from ropes. “At times, it seems like it was all a dream, but the images of the crash site and flashbacks from the horrific firefights… constantly visited my mind,” Shorten reflected. The failure deepened his guilt, pushing him into hobbies like meteorite hunting, restoring Ford Model T’s, and sport parachuting. Yet, as Meyer captures, “the old gnawing feeling returned to his stomach” with every photo glance.

The 2016 Pivot: A Reunion Rekindles the Fire

Late summer 2016: Reviewing 2002 photos reignited the ache. An SOA reunion invite followed—October’s 40th annual gathering of SOG vets. There, Shorten shared his saga with DPAA caseworkers. “Surprised” by the 2002 effort, they listened intently. Shorten’s vow: “If you go back to Cambodia for 1st Lt. Eric James Huberth and Capt. Alan Robert Trent, I want to go with you.” Post-reunion briefings sealed it. By February 27, 2017—at 70—Shorten boarded a flight for Phnom Penh, briefing DPAA on 2002 sights and fresh intel.

The 2017 DPAA Odyssey: Digging with Ghosts at Age 70

Arrival and Setup (March 5–6)

Touchdown in Phnom Penh; a convoy to Ban Lung (airport closed) set base camp. An Australian helo firm—with a female pilot—would ferry them, easing the 23-day hikes of old.

The Daily Grind: Jungle, Shovels, and Hope

For six weeks, the rhythm was relentless: Dawn breakfasts, helo to mountain-top LZs, “killer” hikes down slopes, then all-day digs—scooping soil, screening for clues. Nights rotated: Half returned (Cambodian officer feared ghosts); Shorten often stayed, hammock-bound.

Key days from Shorten’s diary (as shared with Meyer):

- March 8: First finds—“a few related items,” but no breakthroughs for Huberth and Trent.

- March 10: “Possible clues” to the lab—hope flickered.

- March 11: Hike down, more “possibles” (details embargoed till mission close).

- March 14: 3.5 hours’ sleep; 5 a.m. wake-up, breakfast, downhill trek, full-day screen. “Worked all day.”

- March 18: Survival radio antenna unearthed—“still no bones.”

- March 23: Rain-soaked clay defied screens; glass shards only. “Found no bones.”

The toll? Exhaustion at 70—heat, downpours, muscle burn. “Humping up and down steep mountains” tested limits, but Shorten praised the DPAA crew: “The men and women on those DPAA field teams are amazing, dedicated, strong people who take their work seriously. Every day they worked hard. It was heart-warming… In a word, they were awesome.”

A Side Quest: Bonds Across Generations (March 25–26)

DIA Embassy rep joined for a detour: Motorbike to a Montagnard village, ferry across river, then a bumpy ride to a separate helo crash. Shorten negotiated a finder’s fee; locals led to one lab-worthy item. Language barriers amused—Montagnards called all aircraft “simply an aircraft.” Best moment: Flashing 1970 RT photos. “I told them, here are photos of your grandfathers, who were brave warriors. They were amazed… Then they brought us food, beer and we had a grand time.”

Wind-Down and Departure (Late March–April 1)

Markets for carved elephants; rare restaurant meals—“a big deal” after dirt and sweat. Goodbyes to DPAA, DIA, Cambodians, and Montagnards. Bangkok layover: Heavy heart. “No bones… a bitter pill to swallow. It was a long trip home, believe me.”

Reflections: Guilt, Grit, and Glimmers

Meyer’s series nails the duality: 47 years of “swirling, vivid” hauntings—NVA hordes, wingmen’s crushed faces—clashing with Shorten’s unbreakable drive. The 2017 dig yielded fragments (antenna, possibles) but no closure, echoing 2002’s bandit rout. Political snags—Hun Sen’s POW/MIA suspension, border spats—frustrated all. Yet Vietnam’s 2017 access pledges offered hope.

Jim’s story is based on John Stryker Meyer’s masterful seven-part SOFREP series (2017), which chronicles Shorten’s saga with raw detail and veteran insight. You can read the full account here: https://sogsite.com/2021/05/12/james-shorten/

Unanswered Echoes: The SIGINT Shadow, the Forgotten Helmet, and the Silence of the 470th

After fifty-five years of digging through Ratanakiri’s jungle ridges, the story of Cobra 84 (REFNO 1619) still feels unfinished. Jim Shorten’s lifelong quest, the DPAA’s decade-spanning excavations, and the PAVN 470th Division’s iron grip on the Fishhook have all been laid bare in this article. Yet three stubborn questions hang in the humid air like unexploded ordnance: the NSA radio intercepts that say an American pilot was captured, the pith helmet of Lê Đình Sâu that has sat in the case file since 1970, and the complete absence of oral-history interviews with the very North Vietnamese units that controlled the crash site. These are not minor loose ends; they are the cracks where hope, truth, and accountability keep slipping through. In a case that has cost millions of dollars and produced life-support gear but no human remains, why have these leads been left untouched?

The NSA signals intelligence is the loudest unanswered whisper. On the afternoon of May 13, 1970, two intercepts were caught in real time. The first described rifle fire hitting the Phantom as it pulled off the target and slammed into the hillside. The second was blunt: “We captured an American pilot.” No parachutes, no beacons, and the jet had flattened a village—details that line up perfectly with the hooches and cemetery RT Delaware saw the next day. The Defense Intelligence Agency agreed with the NSA’s initial correlation: one of the two crewmen was taken alive. For years the intercepts were classified. When they finally surfaced in 2014, DPAA labeled them “inconsistent” because one phrase said the plane “flew away in flames,” which clashes with the eyewitness account of an immediate crash. Fair enough, but that single inconsistency does not erase the rest of the message. No full Vietnamese language transcripts have ever been released. No voice tapes have been declassified. The raw audio remains lost to time! Shorten himself speculated that the crew could have been thrown clear on impact or dragged from the cockpit. The boot with human tissue—confirmed by Colonel McCowan—hints at a brief window of survival. Why has no one pushed for the unredacted recordings? Why no modern re-analysis of the tapes? If one man walked away from the fire, did he end up in the six or seven graves just 300 meters away, or was he marched north to V211 Hospital? The SIGINT is not dead evidence; it is a live wire waiting to be picked up.

Then there is the pith helmet of Lê Đình Sâu, a name that has been sitting in the case file since the day RT Delaware pulled it out of the carnage. Hand-scrawled inside: “Lê Đình Sâu, HT 6321.” Around the edge, the proud slogan of the People’s Revolutionary Army. A metal badge, an officer’s belt, a canteen, a fatigue shirt, and syringe vials came with it. This is not random gear; it belonged to a soldier in the exact camp where Cobra 84 fell. The 4th Engineer Regiment of the 470th Division built roads, guarded truck parks, and shot at low-flying jets with rifles. Sâu was likely one of them—a logistics man or sapper from Đắk Lắk Province or nearby. His serial number or unit ID etched for all to research. Yet in fifty-five years, no one has tried to find him. Veteran databases in Vietnam come up short for 1970, but the Vietnam Office for Seeking Missing Persons (VNOSMP) has never been formally asked: “Lê Đình Sâu, HT 6321, B3 Front, May 1970.” If he is still alive—possibly in his late seventies or early eighties—he could answer simple questions: Did your squad pull a survivor from the cockpit? Did you rebury anyone in the stone-marked cemetery the Americans saw? The helmet is not a museum piece; it is a direct phone line to an eyewitness. Leaving it untouched is inexplicable.

Finally, there is the deafening silence from the 470th Division itself. Formed just one month before the crash, this 10,000-man unit owned the Fishhook in May 1970. Its infantry ambushed SOG patrols, its engineers bridged rivers, and its logistics hubs fed the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Shorten’s team spotted an engineer unit west of the village—almost certainly the 4th Engineer Regiment. Vietnamese military histories on qdnd.vn praise the 470th for creating a “strategic rear” in the area and claim many American aircraft shot down. DPAA’s 2023 Case Summary approves interviews with B3 Front veterans and V211 Hospital staff, but not a single oral history has been collected from the 470th’s subunits. Stony Beach, the research team that excels at defector debriefs, has never targeted these men. With the 2026 U.S.–Vietnam Comprehensive Partnership opening, there is no excuse left. Commanders like Lê Xuân Bá may still have living subordinates. Truck-park guards, sappers, and medics who salvaged parts of the jet could describe exactly what happened in the hours after impact. Why has no one asked?

These three threads—the SIGINT capture report, Lê Đình Sâu’s helmet, and the untapped voices of the 470th—braid together into one larger failure. Life-support equipment could prove both pilots were aboard at impact, yet the intercepts insist one was taken alive. The helmet points to the PAVN unit; the lack of interviews keeps their story buried. DPAA has excavated over 5,000 square meters, found Trent’s ID tag, and confirmed the crash path across three hills, but the human story remains locked away. For Eric Huberth’s sisters—still wearing his MIA bracelet since 1970—and for Jim Shorten, who has carried this weight since that rotor-damaged extraction, the inaction is personal. The case sits in “Active Pursuit,” but pursuit of what, if the clearest leads are ignored?

The ridge still holds its secrets. One American may have crawled from the flames, only to vanish into the 470th’s grip. Until the raw SIGINT tapes are released, until VNOSMP tracks down Lê Đình Sâu, and until the 470th’s veterans are finally asked what they saw, Cobra 84 will remain a phantom in the Fishhook. Hope keeps digging—but so must the questions no one has dared to ask.