Captain Albert H. Price: A Tale of Lost Love and Unyielding Valor in the Pacific War

In the sultry haze of Mindanao’s jungles, where ancient Moro traditions clashed with the thunder of modern warfare, a young American captain’s story unfolded like a tragic romance from a bygone era. Captain Albert Holt Price, engaged to the love of his life but torn away by the tides of World War II, embodied the heartache of promises unkept and battles unforgotten. At just 24, he faced the horrors of invasion, captivity, and execution, his life a poignant reminder of the personal costs hidden behind history’s grand narratives. As we delve into Albert’s journey, let’s explore the turbulent historical backdrop of the Philippines during WWII—a land of colonial legacies, fierce alliances, and devastating loss—that turned ordinary men into legends and left lovers waiting in vain.

A Southern Boy’s Path to the Pacific: Dreams Deferred

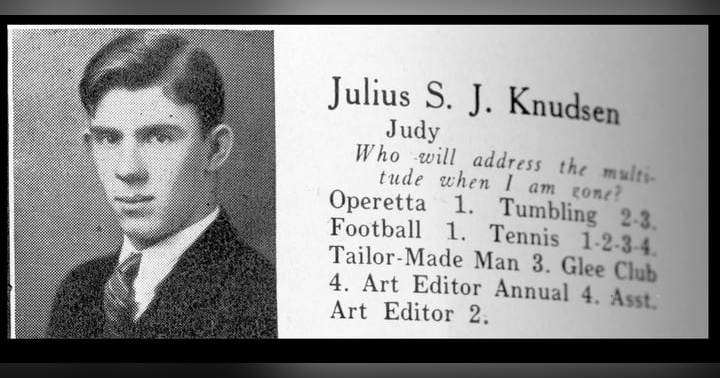

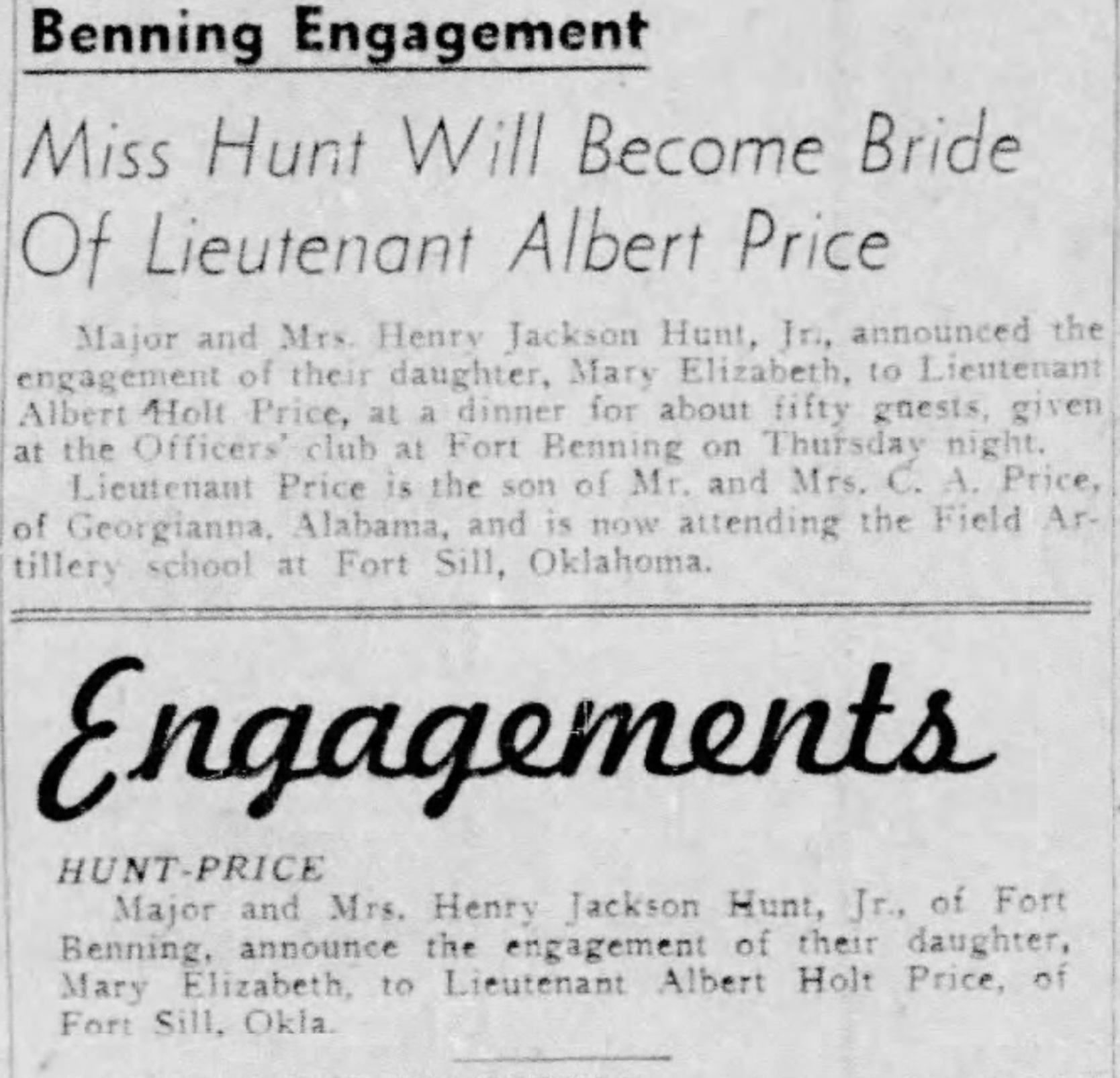

Born on October 15, 1917, in the quiet town of Fort Deposit, Alabama, Albert Holt Price grew up under the vast Southern skies, son of Mr. and Mrs. C. A. Price. His early years were marked by ambition and discipline; at Auburn University, he excelled in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), rising to the rank of major and joining the Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Graduating in 1939, Albert attended Fort Sill’s officer training school, sharpening his skills for a world on the brink of chaos. But amid the drills and textbooks, love bloomed. He became engaged to Mary Elizabeth “Jo” Hunt, a vibrant young woman from a distinguished military family—her father, Colonel Henry Jackson Hunt Jr., was a West Point graduate who would later earn the Silver Star for his own WWII exploits.

The Philippines in 1941 was a powder keg, a U.S. commonwealth since the defeat of Spain in 1898, scarred by the Philippine-American War and the Moro Rebellion (1899–1913). During the rebellion, Muslim Moro warriors in the southern islands, including Mindanao, resisted American rule with legendary ferocity, forging a complex legacy of cultural empathy and conflict. By WWII, these alliances proved vital as U.S. forces integrated Filipino and Moro troops against Japan’s expansionist drive. Albert arrived in this volatile mix, stationed by January 1941 as an infantry battalion commander before shifting to Coast Artillery, guarding airfields near Zamboanga. Living with an American plantation owner who’d called the islands home since 1910, he witnessed the fusion of expatriate life and indigenous resistance—a microcosm of the U.S.-Philippine bond.

In a letter home around June 1941, Albert captured the surreal tension: “This is the darnedest war that you ever heard of. Since the war started I have been on six of the Philippine Islands and so far the only danger I have been in was a strafing raid by four Jap planes in Iloilo City.” Little did he know, the storm was just beginning.

Bravery Amid Invasion: The Fall of Mindanao

Japan’s assault on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, plunged the Pacific into war, with the Philippines as a prime target. While Luzon bore the brunt, leading to the infamous Bataan Death March, Mindanao’s 1942 defense was a gritty saga of endurance. Under Brigadier General Guy O. Fort, a leader who had built deep ties with the Moro people, Albert served in the 81st Division (Philippines). This unit, blending American strategy with local guerrilla tactics, held the line from April 29, 1942, ambushing invaders and demolishing roads to slow the Japanese advance.

Albert’s heroism shone brightest here, earning him the Silver Star, awarded posthumously on March 13, 1946. The citation paints a vivid scene: “Despite these conditions and disregarding danger, Captain Price went forward to an exposed crest under enemy artillery, mortar, and small arms fire, to locate targets. He then returned to his gun to direct its laying and then returned to the crest to adjust fire by arm signals… He continued to fire it rapidly until its capture was threatened, when he destroyed it.” In the pitch-black night, pinned by snipers, Albert ensured his weapon denied the enemy—an act of pure defiance.

Overwhelmed, the forces surrendered on May 27, 1942—not through capture, but as part of a broader capitulation to avert massacre. Yet, resistance simmered; Fort allowed Moro fighters to keep U.S. rifles, sparking underground warfare that harried the Japanese for years.

The Agony of Captivity: A Love Left Behind

Interned at Camp Keithley in Dansalan (now Marawi), Albert endured the brutal realities of Japanese occupation. Viewing surrender as weakness, captors inflicted starvation and violence, flouting the Geneva Conventions. On July 2, 1942, four prisoners’ escape ignited Colonel Yoshinari Tanaka’s fury. Ordering four officers’ executions, he targeted Fort first. In a moment of profound brotherhood, Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Vesey volunteered his life: “They put General Fort at a stake. Colonel Vesey told them to take him down he would take the General’s place,” recalled young survivor Ben Hagans.

As Albert, Vesey, and First Sergeant John Chandler were bound near Signal Hill, one can only imagine the whirlwind of thoughts racing through Albert’s mind in those final, agonizing moments. Standing there, wrists raw from ropes, the humid air thick with the scent of rain-soaked earth and impending doom, did his thoughts drift to Jo—his bride-to-be, with her poet’s heart and artist’s eyes, waiting back home for a letter that would never come? Perhaps he pictured their unwalked aisle, her smile under a veil, the life they might have built filled with laughter, children, and quiet evenings. Or did memories of his family flood in—the warm Alabama sunsets over Fort Deposit, his parents’ proud faces at his Auburn graduation, the simple comforts of home that now felt worlds away? In the face of bayonets glinting under the tropical sun, maybe he clung to visions of Southern fields blooming with cotton, the taste of sweet tea on a porch swing, or the embrace of siblings and friends left behind. These fleeting reveries—tender, defiant—must have been his silent armor, a final act of humanity amid inhumanity, whispering of love and home as the shadows closed in.

Bayoneted in a drawn-out torment, their cries piercing the camp. The next day, survivors faced the Iligan Death March—a hellish trek without sustenance, where the fallen were executed. This overshadowed atrocity, documented in the Tokyo War Crimes Trials, mirrored Bataan’s horrors but fueled Moro revenge attacks. Tanaka was hanged in 1949, but Albert’s death at 24 left an indelible scar—a young life, brimming with love and potential, extinguished.

Echoes of Sacrifice: Bringing Albert Home

Today, Albert’s legacy inspires. This fall, the Asymmetric MIA Accounting Group (AMAG) launches a mission to Mindanao, targeting sites near Camp Keithley with survivor accounts and advanced tools to recover his remains and those of his comrades. It’s a step toward closure, honoring the unbreakable U.S.-Philippine bonds forged in fire. You can help bring him home—donate at AMAG Mission Mindanao .

Join the Legacy

Albert H. Price’s story isn’t just history—it’s a call to remember the loves lost and lives given. Follow Stories of Sacrifice for more, and let’s ensure heroes like Albert inspire forever.

John Bear, Chief of Research - Asymmetric MIA Accounting Group (AMAG) Inc.